But often a worker cuts a corner and puts himself at risk. Why?

There seems to be a space between what a worker knows is safe — and what he actually does in the field.

Maybe if I can figure out what is in this space and give it a name, I can stop scratching my head while I still have some hair left.

Default habits

Dr. Dean Ornish, MD, a prominent heart surgeon, wrote a book, “Simple Changes, Powerful Choices,†in which he talks about his frustrations dealing with bypass heart patients. Many patients came to his office feeling awful. In exchange for years of poor diet, stress and lack of exercise, these individuals had problems breathing and chest pain.After bypass heart surgery, the patient would feel great, better than he had in years. So, instead of following the prescribed post-surgery diet and exercise regimen, the patient returned to the exact same routine that created the heart condition in the first place — back to the bacon, eggs, etc.

Six months later, this patient would return for another bypass.

Bypass surgery is a metaphor for addressing the symptom and not the problem. Heart patients were unwilling to get at the root causes — diet and lifestyle — to live a better, longer and fuller life. Safety-sensitive workers often fall into the same trap.

Workers, safety committees and supervisors treat a symptom with a “bypass†solution. Instead of addressing the need for the individual to change (and follow the prescribed safety rules), a new tool or training session is the chosen solution. That makes everyone feel good — but six months later the training is forgotten and the worker unchanged, continuing to work at-risk.

Wrong kind of PPE

As the 2002-2003 National Basketball Association season drew near a close, Michael Jordan was fighting for a playoff spot. His Washington Wizard teammates, however, were not. After one partially frustrating one-point loss to the New York Knicks, Jordan lambasted his teammates.“It’s very disappointing when a 40-year-old man has more desire than a 24-, 25- or 23-year-old, diving for loose balls, busting his chin and doing everything he can to get his team into the playoffs. Until guys let go of that macho, cool attitude and do the necessary things… it’s sad when we’re not doing that when we’re at a point of urgency,†Jordan said in disgust.

The same can happen on the shop floor. Workers in safety sensitive jobs do the safety equivalent of failing to dive after loose balls. Why?

Tucked neatly in that space between what’s safe and what’s actually done on the job is a Kevlar vest. Each suggested change in behavior is either aggressively or quietly disregarded. Why change when you think you’re bulletproof?

Well, the problem with deflecting at-risk behavior with Kevlar is that one morning before work you’re running late because you forgot to set your alarm. In this morning commotion, you’ll remember your lunch box but forget your Kevlar vest.

I send my condolences to the family.

Our safety identity

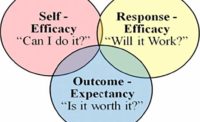

So, just what is this void between what workers know is right and what they actually do? It’s called the safety soul. Each of us has a safety soul. After a worker is trained, skilled and knowledgeable, it’s the safety soul — weak or strong — that determines the size of this space.To improve the safety soul we must turn our attention away from the catastrophic — no one ever thinks it can happen to him or her. We must turn our attention away from telling workers, “You must do or else.†To improve the safety soul, workers must realize and become a believer in the positive benefits of safe work.

I want to share an exercise with you. Close your eyes. Now, point to yourself.

What did you point to?

More than 99 percent of us point to our heart. It’s interesting, because we don’t point to our head or our hands. No, we point to the heart, or the soul.

We’re not safe because of our heads (the rules we know) or our hands (the procedures we follow). We’re safe (or unsafe) because of the size of our safety soul.

Remember, safety for our safest workers is an attitude that reflects life and life’s importance. A more soulful approach to safety, then, centers on activities that make us think or reflect on life and safety.