Lightning storms had delayed flights coming into and out of Orlando, where I had been for a safety conference. Once my flight to Charlotte finally took off, I wondered if I’d make my connecting flight to Roanoke and get home that night. Passengers behind me were also sweating the minutes. Their flight to Nashville would depart at 10:45 p.m., and it was almost 10:40 when we arrived in Charlotte. I told them not to worry; surely their aircraft would wait a few minutes. Numerous times I had been on flights that waited at the gate for late arrivals.

I hustled off the plane, but to no avail — my flight to Roanoke was already in the air. While I waited for my ride to a hotel, I was surprised to see one of the passengers with a Nashville connection also waiting for the hotel van. It turns out he and seven other passengers on my Orlando flight got to the gate for the Nashville departure right at 10:45 p.m. Two teenagers in his group had actually reached the gate a few minutes earlier, running ahead to tell the gate attendants of their arrival. But the plane to Nashville had already pulled away, four or five minutes before the scheduled departure time.

“We were there on time, so why didn’t they wait?” my fellow stranded traveler wanted to know. As you might imagine, he rather passionately expressed his displeasure. We both recalled times when flights were held up waiting for delayed passengers. Why not this time?

(Incidentally, when my flight to Roanoke left the gate the following morning, I checked my watch. It read 10:46 a.m. — and the flight was scheduled to depart at 10:50 a.m.)

What gets measured ...

I think I know what’s going on. Think about how airlines are ranked. What measure is used to define public opinion about the different carriers? The index I hear most often is the average delay in departures and arrivals.Could it be that a top-down management focus on gaining a high ranking for “timeliness” influences a disregard for customers trying to make a tight connection? Might a flight crew actually try to leave the gate early in order to shave a few minutes off the mean gap between scheduled and actual departures? If this outcome measure is a key indicator of success, as defined by airline management, the answer to these questions is a definite “Yes.”

The hidden cost

I think the measurement or accountability system used today by airlines is a major reason why so many people complain about air travel. Outcome numbers — ranging from profits to media rankings based on timely departures and arrivals — motivate airline management and employee behaviors that contribute to negative customer attitudes. But since all the complaining doesn’t seem to affect the bottom line —Newsweekreports a record 665 million people are expected to book flights this year — why should airlines worry about a relatively few disgruntled customers?To keep customers happy and avoid ugly and dangerous episodes of air rage, airline personnel should do everything possible to please, even delight, travelers. Negative experiences surely decrease the number of customers, right? And increasingly frustrated passengers lead to more incidents of aggressive behavior. In fact, I was recently interviewed by a newspaper reporter about “air rage” — attacks on flight attendants and pilots that unfortunately seems to be a growing and alarming trend. One passenger recently rushed into the cockpit and bit the pilot on the arm.

So what can airlines do?

- Wait a few minutes for delayed connections;

- Cover the lodging expenses of stranded customers;

- Announce information as soon and as completely as possible regarding delayed incoming or outgoing flights; and,

- Provide sufficient

personnel during “emergencies” to help customers reschedule flights and

find suitable interim accommodations.

Back in the workplace

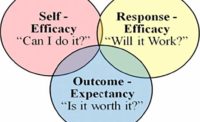

I’m sure safety leaders see the relevance of this story. And it’s more than the fact that air rage presents a safety hazard. As you know, a preoccupation with outcome numbers in safety can lead to the same kinds of complaints and frustrations that air travelers vent.The popular phrase, “what gets measured gets managed” is unfortunately true. So when injury rates or compensation costs are the key — or only — indicators of safety success, you can expect limited attention will be paid to activities that do not directly and immediately affect these numbers.

Pilots can be motivated by outcome numbers to leave the gate early. Likewise, some employees will hide injuries when the focus is on OSHA recordables. Sometimes these actions are explicitly supported by a safety incentive or bonus system.

We shouldn’t ignore how frustrations and complaints — overall attitude and morale — influence the safety and health of an organization. It’s just like their impact on the pleasure and safety of air travel.

What should we do about it?

If you have a travel tale like mine, I’m sure you can list a number of ways — call them basic process activities — to reduce frustration and anger. The same can be done at work to improve attitudes and morale regarding safety. Most of these steps, including continuous and caring interpersonal conversations, will not be monitored or measured. But we do them anyway because they are the right thing to do. Our emotional intelligence tells us that, in the long run, caring behavior will benefit people’s safety and health. And if we extend this kind of actively caring behavior beyond the confines of our work setting, we give others — including airline personnel and passengers — opportunities to learn from our example.