The root cause lies in the measurement system. It creates a blind spot, not giving visibility to the events necessary to see in order to prevent serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs) and catastrophic events.

Chief executives and other leaders often assess safety performance solely on the basis of OSHA injury rates — or large penalties. Unaware of the limitations of injury rates alone, they feel ambushed when serious injuries and fatalities occur.

The catastrophic incidents of 2010-11 — the Tesoro refinery explosion in Anacortes, Washington, April 2, 2010 (5 workers killed); the Massey Energy Upper Big Branch mine explosion April 5, 2010 in West Virginia (29 miners killed); the BP Deepwater Horizon explosion in the Gulf of Mexico April 20, 2010 (11 worker deaths); the PG&E pipeline explosion in San Bruno, Calif., September 9, 2010, (4 employee deaths); and the entrapment of 33 miners in Chile from

|

| Figure 1 |

August 5, 2010 to October 13, 2010 — are worst-case examples of this lack of leadership understanding of true root causes, and the disconnect between the board room and the safety professional.

In virtually every instance, the headline-grabbing catastrophe was preceded by years of low, sometimes very low rates of recordable injuries. Asked, “How is your company performing in safety this year?” most executives on the watch during these incidents would have answered: “We’re doing great. Our injury rates are lower than ever.”

This profound confusion has dire consequences. The relationship between minor and severe injuries, between employee safety and process safety, and the meaning of non-injury events with high potential for serious injury, fatality or catastrophe, is much more complex than what can be gleaned from a glance at recordable rates.

In the aftermath of these catastrophes, senior leadership is often exasperated and fatalistic, a reaction dating back years:

- “We have done all we can to prevent catastrophic failures like this one,” said Armand Hammer, CEO of Occidental Petroleum in a televised interview on July 7, 1988, following the Piper Alpha disaster resulting in 167 worker deaths.

- “Sometimes you step off the curb and get knocked down by a bus,” said Tony Hayward, then CEO of BP, July 28, 2010, as quoted in the United Kingdom newspaper, The Independent.

- “Accidents sometimes happen,” said Don Blankenship, then CEO, Massey Energy, at a press conference on April 26, 2010.

- “We don’t know where these events are coming from, we don’t see a pattern,” said a steel company CEO at public forum in 2010 discussing a recent rise in fatality rates.

A nationwide plateau

What is perplexing, not only to CEOs, but safety and health leadership across U.S. industries, is the stubborn persistence of serious injuries and fatalities.

For this article, SIFs are defined as any event that results in a fatality; a life-threatening injury or illness that if not immediately addressed is likely to lead to death (such as severe burns or damage to the brain or spinal cord); or a life-altering injury or illness resulting in permanent or long-term impairment (such as amputations or paralysis).

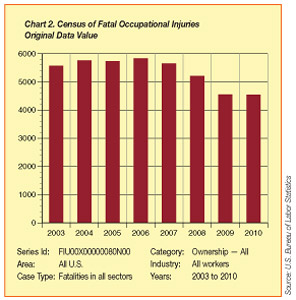

On August 25, 2011, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) announced that “a preliminary total of 4,547 fatal work injuries were recorded in the United States in 2010, about the same as the final count of 4,551 fatal work injuries in 2009.” The number of fatal work injuries in 2009 and 2010 reflects an insignificant change. (See chart.)

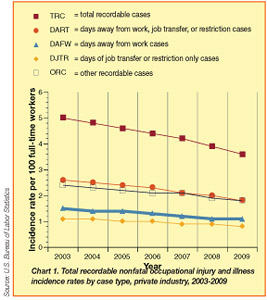

Cases involving days away from work, the most serious injuries, also have proven difficult to improve nationwide. In 2009, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 965,000 DART cases (cases involving Days Away From Work, Job Transfer or Restriction Cases). In 2004, there were 1,259,000. But in the intervening years, severe economic recession and high unemployment, particularly in the dangerous fields of construction and manufacturing, have skewed the numbers. (See chart.)

|

| Figure 2 |

Another factor masks the true incidence of serious injuries. According to the BLS, for the past 12 years in manufacturing, the rate of job transfer or restricted work cases has exceeded cases involving actual lost workdays. In part this reflects economic pressures forcing companies to try to contain healthcare and medical costs, and aggressive return-to-work programs.

Leading companies are tracking the “Serious injury rate.” This is usually defined as the number of fatal and serious injuries divided by hours worked.

Challenging Heinrich

The statistical pattern seen in the BLS data and in many individual companies calls into question one of the core assumptions of modern safety science. For the past 80 years the safety community has assumed that the Heinrich Safety Triangle (HST), first introduced in 1931, is an accurate depiction of the relationship among types of injuries, and how to prevent SIFs.

William Herbert Heinrich was an assistant superintendent of the Engineering and Inspection Division of Travelers Insurance Company when he published his landmark book, Industrial Accident Prevention: A Scientific Approach. His theory predicts that for every 300 near-miss incidents there will be 29 minor and one major injury. The theory is descriptive: frequency and severity are inversely related. And predictive: reductions in smaller injuries will result in proportionate reductions in more serious injuries.

What the BLS data has shown in the past decade — declining smaller injuries at the same time serious injuries and fatal injuries remain level or show increases — directly refutes the HST predictive theory. Reductions in less serious injuries have not produced reductions in more serious injuries. Still, many executives rely on metrics thought to be predictive based on the HST to assess the strength of their safety management capability.

John Mogford, at the time senior group vice president, safety & operations, for BP, conceded this blind spot in 2006 in his speech to the Center for Chemical Process Safety, 2nd Global Congress on Process Safety: “Do not get seduced by personal accident measures; they have their place but do not warn of incidents (Editor’s note: such as the BP Texas City refinery explosion). There is a need to capture the right metrics that indicate process safety trends.”

Organization leaders must accept that the Heinrich triangle is not accurate predictively. The causal factors for serious injuries and fatalities are different in kind than those that underlie non-SIFs. It is implausible that a serious injury event is a fluke. Or a one-time employee mistake. (Heinrich claimed 88 percent of all workplace accidents and injuries/illnesses are caused by “man failures.”) It is erroneous to assume the conditions leading to a SIF have never previously occurred. SIFs have identifiable precursors. Identifying them on an ongoing systematic basis is fundamental to effective intervention strategy.

A precursor is a high-risk situation in which the exposure controls are either absent, ineffective, or not complied with, and if allowed to continue or repeat, could reasonably result in a serious injury or fatality.

Reducing the number of incidents at the bottom of the triangle does not necessarily reduce the number at the top in a proportional way. Our studies of clients has shown the potential for a fatality or serious injury is highly variable across the range of less serious injuries that occur, reflecting the fact that SIF potential varies among different types of risk exposure. (For example, a back strain from lifting a load has little SIF potential, while a fall from an elevated work position has high SIF potential.) As a result, an initiative can be highly effective in reducing the number of injuries with low SIF potential while having little or no impact on the exposures with high SIF potential.

Organizations operate with limited resources to devote to safety. Given these constraints, it is essential that resources be allocated in such a way as to have impact on serious injuries and fatalities as well as less severe injuries. For example, safety observations should be targeted to high-risk potential situations, and observations alone should not be assumed to cover all high risks.

High-risk precursors

Specific types of work activities and safety controls are most closely associated with incidents that have SIF potential, according to industrial root cause analysis research, BLS data, and healthcare research of medical errors. For example, injuries involving equipment and pipe opening of hazardous chemicals, lock out/tag out, machine guarding and barricades, confined space entry, and use of hot work permits tend to have SIF potential, as do operation of mobile equipment, water craft, working under suspended loads, and working at elevations. Examining the high-risk exposures for a specific company or location can identify exposures with high SIF potential, allowing the design of interventions that focus on those exposures.

The occurrence of a major SIF event requires a special and infrequent configuration of factors. A variety of conditions must occur and the safety controls designed to protect against injury must fail. A series of things all must occur, and each of these things individually has a low probability. A pipe must leak, and contain flammable material, and no one reports the leak, and no inspection identifies it, and the leaking material finds an ignition source, and there is a fire. The odds are slim that the first and only time a pipe leaks it contains flammable material, and it goes unreported by everyone, and it isn’t noted in an inspection, and the leak is near an ignition source. It is much more likely that leaks have occurred often, and reporting of them is sporadic, and inspections are not comprehensive, so eventually one of these leaks is a flammable material leaking near an ignition source. The underlying high-risk exposure has occurred many times before.

Restricted awareness

Many organizations, particularly global multinationals we have worked with and studied as consultants, are aware of non-SIFs that have high potential. This was brought home in a 2008 study by the safety and health consultancy Mercer (formerly ORC Worldwide). But few organizations possess the requisite tracking and data collection needed to address precursors in sustainable ways. This was emphasized by Fred Manuele in a 2008 article in Professional Safety, “Serious injuries & fatalities: A call for a new focus on prevention.” Since OSHA Total Recordable Incident (TRI) rate changes are not indicative of changes to SIF potential, in the absence of measuring incidents with SIF potential, organizations have no way to assess whether they are making progress in reducing the exposures that contribute to SIFs, according to Manuele.

Intervention principles

In designing interventions to address SIFs, these principles should be followed:

- SIF potentials — the combination of actual serious injuries and fatalities with less serious injuries that have SIF potential — should be tracked as a separate outcome metric. This can be done by studying data on exposure, often found in reports of injuries. In addition near misses, safety observations and audit findings should be used to identify precursors.

- Intervention to reduce SIFs should be a process that engages employees at all levels, uses data analysis to understand sources of precursors and provides sustainable mechanisms to identify and address precursors. This is not a one-time activity but an ongoing process. Implementation of the process should occur within a change management framework. Behavioral observation systems should ensure a strong link to Cardinal Safety Rules and high-risk exposures. Both the design of safety systems targeting SIFs (their integrity) and the quality of how they are implemented (conformance) should be addressed.

- Intervention design should include data drawn from process safety. This is particularly important. Many organizations do not make the critical distinction between employee safety and process safety. Personal injury and illness rates are considered paramount and process safety data is often neglected. Data from significant operational upsets, design flaws, catastrophic fires and other related variables should inform the strategy.

- Senior leadership should understand and lead the intervention. Leaders should set measureable objectives and gather baseline measures, inform leaders of the overall SIF prevention initiative, and assess senior safety leadership capability and provide feedback. Tie to roles in leading the intervention.

- Existing systems for SIF prevention and previous studies and interventions to prevent SIFs should be reviewed.

- A data tracking system to measure the rate of SIFs and high potentials should be designed and implemented.

- All data should be examined in search of precursors, including incidents, near misses, safety observations, audit findings and interviews with employees. Include process safety exposures as well as personal safety exposures.

- Precursors of SIFs are readily identifiable from longitudinal analysis (correlational research involving repeated observations of the same events over long periods of time) of available data. But most organizations do not have consistent visibility of this data because it is buried in the category of “recordable injuries” without distinguishing those with high and low potential for SIF, a point made in Manuele’s article.

- Integrate the precursor identification and remediation process with existing systems: audits, safety observations, and other safety systems.

- Conduct focus groups with cross-sections of employees to inquire about their perceptions of the integrity and conformance of the safety systems designed to protect them from SIF.

- Define specific roles in behavioral terms for each level of employee throughout the organization.

The intervention should show measureable results within the first one-year period from the time of deployment. And the intervention should be sustainable in the long term.

Correcting serious flaws

As the BLS statistical trends indicate, serious flaws exist today in the way many organizations address SIFs. Many are aware of non-SIFs that have high potential, but few have the consistent visibility needed to address precursors in sustainable ways, according to a Mercer/ORC Worldwide 2008 study of member companies, summarized in a November, 2008 article by James Nash in ISHN, “Preventing death on the job: Did Heinrich get it wrong?”

Companies that do track SIFs find that it represents a bright line of differentiation from other types of injuries, writes Nash in the ISHN article. Losing your life, your sight or mobility, or other injuries of similar magnitude, are different in kind from injuries that heal without life-changing consequences. Of course companies want to reduce and eliminate all injuries. But safety resources should be deployed in a way that reduces all levels of severity.

Unless this issue is addressed we will likely continue to see the disheartening pattern of decreasing smaller injuries yet level or increasing SIFs. Lack of visibility makes it unlikely that the factors underlying SIFs will be addressed effectively. The kinds of things most organizations are doing presently will not provide the visibility needed to address the issues underlying SIFs. Doing more of the same is not going to reduce SIFs. Intervention is needed to change the course and direction of how resources are used in order to affect them.