It also explains the special challenges of promoting safety and health in the workplace. You see, at-risk and unhealthy behaviors are often followed naturally by immediate and pleasant consequences-comfort, convenience, excitement, sensory stimulation. In contrast, safe and healthy behaviors are usually accompanied by inconvenience, discomfort, or boredom.

Plus, the presumed benefits of safe and healthy behaviors are either not experienced-no incident occurs to demonstrate the protection of PPE-or benefits are too delayed or uncertain to have much impact on current behavior. For example, the physical benefits of exercise and nutrition are usually noticeable only after substantial time and effort.

Here are various types of consequences:

Natural consequences

Motivating consequences are inherent or intrinsic to the ongoing task. In other words, behavior is often followed naturally by supportive or nonsupportive consequences. Athletic behaviors from bowling and golf to basketball and tennis result in immediate consequences that provide invaluable feedback for improving performance.

Creating a consequence

But since task-intrinsic consequences are not usually available to support safe and healthy behaviors, it is often necessary to add extra consequences to keep the desired behavior going.

Often the most powerful consequence is personal and genuine recognition or appreciation. Interpersonal coaching feedback after a behavioral observation exemplifies the use of extra consequences to sustain desired behavior. Reminding people that their safe behavior sets an important example for others can go a long way to keep safe behavior going.

Inner motivation

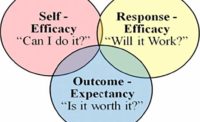

These intrinsic and extra consequences are external to the participant, they can be observed by another person. Behavioral scientists focus on these types of consequences to evaluate and develop motivational processes because they are objective and scientific. But behavioral scientists do not deny the existence of internal determinants of motivation and action. There is no doubt that we talk to ourselves before and after our behaviors, and this "self-talk" influences our performance. We often give ourselves internal verbal instructions before acting, and afterward we often evaluate our performance. We might motivate ourselves to continue the behavior-with self-commendation-or to discontinue the behavior-with self-condemnation.

Internal consequences to support the right behavior are terribly important when it comes to safety and health. As mentioned, external and task-intrinsic consequences for safe and healthy behaviors are not readily available, and we can't expect others to keep us making proactive, safe, and healthy choices. So we need to talk to ourselves with sincere conviction, and with genuine self-reinforcement, when we do the right thing.

We need to savor special external consequences for our efforts whenever we receive them, and use this recognition or feedback later to bolster our self-reinforcement. Often it's useful to hear about the special consequences experienced by others for their safe and healthy behaviors. We can relate these success stories to our own situations to keep us going.

The following case study might help you justify certain proactive behaviors, such as actively caring for safety, while also illustrating the motivational role of various types of consequences-intrinsic versus extra, and internal versus external.

The 'Airline Lifesaver'

Since November, 1984, I have been using a proactive intervention behavior whenever I board an airplane. I hand the flight attendant an "Airline Lifesaver" card that asks the recipient to announce this statement near the end of the flight:

"Now that you have worn a seat belt for the safest part of your trip, the flight crew would like to remind you to buckle-up during your ground transportation."

This small act is rewarded with a natural consequence whenever the announcement is made, which has been relatively often. From November, 1984, to January, 1993, I distributed the Airline Lifesaver on 492 flights, and 36 percent of the time the flight attendant gave a public buckle-up reminder. From March, 1994, to February, 1995, I gave the Airline Lifesaver to 118 flight attendants and was rewarded with a buckle-up reminder on 54 percent of these flights.

Why did I separate the two time periods when reporting these results? And what could account for the significantly higher announcement percentages during the second time period?

Well, I used different Airline Lifesaver cards during these periods. The cards distributed during the first phase merely requested the buckle-up announcement, whereas the new cards (used during the second phase) offer prizes valued from $5 to $30 if the buckle-up reminder is given. If the announcement is made, I give the attendant a postcard to mail to my office in order to redeem a reward. To date, of the attendants who received this extra consequence, 65 percent stamped and mailed the postcard.

So what types of motivation and rewards are involved here? The value of the extra consequence in motivating flight attendants to give a buckle-up reminder is demonstrated by the high percentage of postcards mailed to my office, and by the greater percentage of flight attendants making the safety announcement when prizes were offered.

Recording the results of this safety intervention at the end of each flight and later tallying the percentages gives me feedback (natural consequences) to keep me going. Feedback graphs depicting percentages of buckle-up reminders per 10 consecutive trips have been a primary motivator for over a decade of using the Airline Lifesaver.

Often the most powerful consequence is personal and genuine recognition or appreciation.

But I must admit I've been tempted to avoid this intervention on some trips, especially when I'm tired and have to rush to make the flight. On these days I ask myself whether the personal expense of the prizes and the extra effort involved in administrating this reward contingency is worth it. It's on these occasions that internal intentions and consequences are important. I need to tell myself it's worth it, and anticipate the consequences of adding to the feedback graphs. But most importantly, I need to convince myself that a buckle-up announcement on an airplane could result in more safety belt use in vehicles and maybe prevent an injury or safe a life.

Many of my friends have laughed at the Airline Lifesaver, and claimed that I'm wasting my time. A common comment is, "no one listens to the airline announcements, and even if they did hear the buckle-up reminder, do you really think it's enough to get them to buckle-up if they don't already use a safety belt?"

I had one personal experience that motivates me to answer "yes," and I remind myself of this story whenever I begin to doubt my proactive safety efforts. I once observed a woman approach the driver of an airport bus and ask her to "please use your safety belt." The driver immediately buckled up. When I thanked the woman for making the buckle-up request, she replied that she normally would not be so assertive but she had just heard a buckle-up reminder on her flight, "and if a flight attendant can request safety belt use, so can I."

The best motivation

Of course, the primary purpose of promoting safe and healthy behaviors is to prevent injury or improve a person's quality of life. Unfortunately, we rarely see these benefits, so we need motivation through feedback consequences, interpersonal approval, and self-talk. We tell ourselves that we're doing the right thing, and that someday an injury will be prevented. We usually can't count the number of injuries prevented by our efforts, so we just need to "keep the faith."

On December 28, 1994, I received a special letter from Steven Boydston, assistant vice president of Alexander & Alexander of Texas, Inc., that helps me "keep the faith" that the Airline Lifesaver and other proactive efforts for safety do make a difference. The essence of this letter is given below, as a success story you can use to keep intervening for industrial safety and health. It worked for me.

THANKS!!! On December 11, 1994, I was a passenger on Flight 499 from Houston to San Francisco. At the end of the flight the pilot came on the speaker and said: "Now that the safest part of your journey is over and you are about to make the most dangerous part of your journey, please remember to use your seat belt...." I may have the words a little off, but I think you know the message. This was the second time I had heard the message. The first was at the ASSE Professional Development Conference in Dallas.

I am an obsessive seat belt user but when I got into the taxi, the seat belt was, as usual, buried in the seat. Usually when I find this in a cab I say, "the heck with it," but I can honestly say the pilot's message motivated me and I "dug out" the seat belt.

At over 70 mph the taxi hydroplaned and struck the guard rail. Thank God for the new barriers that prevent cars from being thrown back into traffic. Thank you and the pilot for the reminder. My wife and children are also grateful. I suffered a neck and shoulder injury-I think it is relatively minor. It could have been much worse. I should mention the driver was O.K. He was wearing his seat belt.

Conclusion

Although "pop psychology" might emphasize that we motivate ourselves with goals or intentions, the fact is that behavioral consequences actually motivate our activities. We behave in certain ways to achieve pleasant consequences or to avoid unpleasant consequences. Goals and intentions are motivational when they anticipate consequences achievable from the goal-directed behavior.

Some consequences are inherent or intrinsic to the task at hand, such as the immediate results of swinging a golf club, baseball bat, or tennis racket. These consequences are sufficient to maintain performance as long as the frequency or intensity of the pleasant outcomes overpower any unpleasant outcomes.

Some behaviors are followed intrinsically by more unpleasant than pleasant consequences. The immediate discomfort or inconvenience outweighs any observable benefits, thus extra consequences are needed to sustain appropriate behavior. One of the most powerful, yet inexpensive, consequences is interpersonal approval or disapproval. Ponder for a moment how much you do everyday to gain or maintain appreciation from people in your life space, and the power of genuine social attention in managing safety becomes obvious.

Considering the role of intrinsic and extra consequences in motivating our everyday behavior implies "thinking," which is essentially self-talk. We talk to ourselves when solving problems, planning actions, writing manuscripts, and evaluating outcomes. Internal consequences are critical to motivating behaviors, especially when external consequences (intrinsic or extra) are unavailable or delayed.

In safety management, hearing the achievements of other persons' proactive behavior provides ammunition for our own self-talk about motivational consequences. Sharing success stories is the sort of motivating consequence that will keep us all talking up safety.