You couldn’t ask a more polarizing question. OSHA chiefs admired by business for their restraint have left labor disappointed if not outraged. OSHA bosses who have enjoyed labor’s support have been the scourge of business.

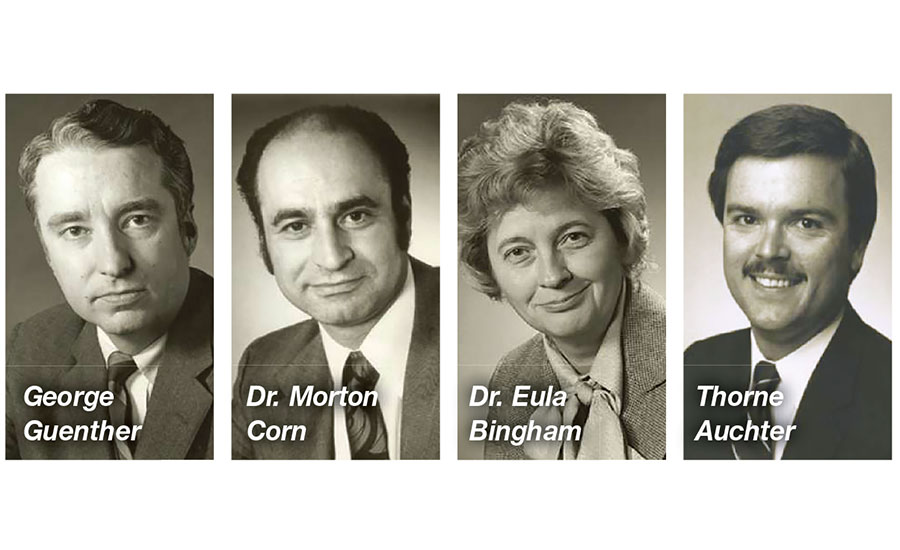

George Guenther (1971-1973) came first. The one-time head of a hosiery business in Pennsylvania oversaw OSHA’s startup. Given the agency’s miniscule budget and vast mandate (covering five million workplaces), the launch was relatively smooth. But with the verbatim adoption and sometimes unreasonable enforcement of a body of voluntary consensus standards developed by industry associations, OSHA gained lasting notoriety as a “nit-picker.”

John Stender (1973-1975) came next, an official of the Boilermakers Union with no safety and health experience. He doubled the standards-setting staff and said that while Congress did not set up OSHA “as a Gestapo,” strict enforcement would be used when necessary. Under the watchful EYE of Congress, the agency began its delicate balancing act of being enforcer, regulator, and compliance consultant. The effort was doomed from the start, and by 1975 OSHA’s credibility and competence were attacked by all sides – business, labor and Congress.

To mollify critics, Dr. Morton Corn, a professor of occupational health and chemical engineering at the University of Pittsburgh, became the first safety and health professional to head OSHA, appointed in 1975. Outspoken and articulate, Corn believed “the very survival of OSHA” was at stake. He worked to restore the agency’s credibility —“a slow climb to quality” he later called it -- and directed more of its focus on health issues, but his short term in office was pressured by 1976 election-year politics.

Dr. Eula Bingham, an occupational health scientist at the University of Cincinnati, appointed by newly-elected President Carter in 1977, to this day is the most respected OSHA administrator in the minds of many labor union safety and health officials. Well aware that “OSHA was about some silly things,” Bingham embarked what she called "an all-out effort to combat occupational illnesses and disease." Inspectors looked harder for serious hazards. In her first two years, OSHA set new standards for cotton dust, lead, benzene and three other industrial chemicals, and proposed or revised a number of safety regulations. In 1980, the agency confronted its most fierce attack from Congress in a bill, ultimately derailed, that would have exempted from safety inspections all employers with a good safety record.

Ronald Reagan’s ascendency to the White House in 1980 turned OSHA sharply in the direction of “regulatory relief.” In 1981 Reagan nominated the 35-year-old vice president of a family-owned construction company in Florida, Thorne Auchter, to run OSHA. To business’s relief and labor’s angst, corporate management came to the agency. Still, widespread and longstanding business criticism of OSHA’s combativeness and cost of compliance threatened its existence. Auchter, working often from six in the morning to eight or nine at night, felt he was operating in a “goldfish bowl.” When he resigned in 1984, he said, “The agency is a growing and learning thing and really is an experiment.” Part of the experiment was establishing the Voluntary Protection Program (VPP) in 1982; another was issuing the landmark hazard communication rule in 1983 – the “soft vs. hard” balancing act epitomized.

Part 2 will appear in ISHN’s May issue