Within the scope of the modern workplace, frequency of hazard exposure is relatively agreed-upon. For any given job role, one can analyze what tasks fit into that role, break the tasks down into Job Safety Analyses, and break down the Job Safety Analyses into particular hazards. Those particular hazards can then be assessed for their rates of exposure to employees.

Severity, however, is a little trickier. For example, severity to the individual employee may be considered catastrophic. In healthcare, a back injury from an unfortunate patient movement could literally end a nurse’s career. But in the scope of the entire hospital, while this injury is extremely severe to the nurse, it will not stop the hospital’s operations. For the hospital, this would not be considered severe to the overall scope of operations.

That said, other hazards could very well stop a hospital’s operations -- Ebola made worldwide news in the fall of 2014. One single Ebola patient had and has the propensity to completely change the flow of operations in an Emergency Department.

In another example, a single chemically contaminated patient brought in by a medevac helicopter can lead to the mobilization of a decontamination team and stagnate helipad operations.

These situations are severe to the individual employee – communicable diseases and chemical contamination are certainly hazardous to employees – as well as the hospital itself in that they can literally change the way the hospital operates.

When one of these situations leads to an Incident Command System (ICS) or even National Incident Management System (NIMS) response, the stakes get even higher. In addition to the impact on operations from potential injuries, exposures, illnesses and operational needs, the relative size of an emergency situation generates possible media coverage, reputational effects and more. The severity of this level of emergency situation can extend well beyond employee injuries. This same phenomenon exists in every industry, albeit with different hazards in question.

The Ebola contingency

Might this be the reason for much organizational delineation between safety and emergency management?

During the fall of 2014, many hospitals underwent a rapid, costly and comprehensive preparedness process for possible Ebola patients. After all, the consequences for failure to prepare for a contingency of this kind include: 1) potential employee exposures and/or illnesses; 2) patient care limitations; 3) contamination control issues; 4) infection prevention issues; and much more. Consider, too, the windfall of news coverage that trailed the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas after their Ebola situation broke in September of 2014.

Health hazard prevention steps

Aside from worldwide news coverage, what separates Ebola from any other communicable disease, bodily fluid or bloodborne pathogen hazard? In any of these types of cases:

- Hazards are required to be identified and analyzed.

- Employees who are at-risk of potential exposures to the hazards must be trained on the hazard and appropriate hazard controls.

- Hazard controls not strictly defined by OSHA or national consensus standards are still subject to the OSH Act’s General Duty Clause.

- Due diligence through the Hierarchy of Controls is necessary, as is paying attention to human factors such as ergonomics and Larry Wilson and Gary Higbee’s “Dangerous States of Mind” and “Four Critical Errors.”

- It’s necessary to communicate these hazards and their reciprocal hazard control on a consistent and recurring basis.

- Leading indicator measures such as: 1) observations to validate safe behaviors through hazard control use; and 2) inspections to ensure safe conditions can help measure participation in the safety program as well as the levels of safe behaviors and conditions.

- Reported near-miss events can be analyzed with causal factors corrected.

- All accidents and incidents require investigations and follow-up to ensure preventative and corrective actions; those actions can be reported back to a Safety Committee or similar team to include them in the ongoing hazard analysis for continual improvement.

Ebola is not an exception

These processes are the same whether the hazard is Ebola, influenza, a blood splash or even a slip, trip or fall. Some say that Ebola is more deadly than Influenza, but influenza will kill more in any given year. Blood splashes carry possible Hepatitis B/C or even HIV. With this, why is it that hospitals made it an urgent matter to specifically implement stringent hazard control expectations for Ebola when any given number of hazards can carry the same severity?

The hazard multiplier

In reality, despite the false dichotomy between emergency management and safety, every hazard exposure is a dry-run for an emergent situation. Aside from the fact that many other hazards are just as severe as Ebola or other emergency situations, failure to work safely on an everyday basis is a negative indicator on emergency preparedness. Consider:

- If employees fail to avoid slips, trips and falls on a regular day, what will happen when the Emergency Department is full of extra equipment and the pace becomes more hurried?

- If employees fail to work safety with needles on an everyday basis, what does that say for needlestick prevention during operations with heightened stress, faster paces, increased fatigue and overall frustration?

- And if employees are injured or ill and out on lost time or on restricted or transitional duty, how will they perform their essential functions when an emergency situation presents itself?

Not only is every situation potentially hazardous, but complacency in everyday situations negatively impacts capabilities to respond to emergencies. Regardless of perceptions and media sensationalism, safety is emergency preparedness.

How to achieve integration

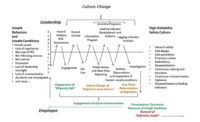

Safety must exist at all levels of the organization. Leaders must implement the program and its expectations and employees must utilize the basic Job Safety Analysis principles to identify hazards in their work and utilize the appropriate hazard controls.

In many cases, hazards don’t wait in the inner-workings of a task but come in with patients such as communicable disease exposures and workplace violence. With this, conditioning and ingrained situational awareness are integral to even identifying these hazards, let alone utilizing the hazard controls before an exposure takes place. This same situational awareness is needed to identify an Ebola patient as is it to identify a potential workplace violence threat. Note that violence is not always a worst-case active shooter – much more common is a patient taking a swing at a nurse.

Colonel John Boyd’s Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) Loop -- traditionally used in combat aviation, later used in ground combat and now used in emergency management – is a wonderful tool in this challenge.

These safety tenets are the preceptors to emergency preparedness – when enough safety issues come to light, they amount to the need for a larger-scale response. If we’ve failed to work safely during this build up, there won’t be enough capability to handle an emergency situation. The two are not mutually exclusive.

Ultimately, safety is not the throwaway that gets tossed when a situation becomes an ICS response. If safety isn’t integrated and hardwired in each of these capabilities and more, operational capabilities may fail at the most inopportune time. When the two are integrated, there’s no choice – safety is preparedness, efficiency and effectiveness. There’s no difference.