Posted with permission from Confined Space, a newsletter of workplace safety and labor issues.

One of the fathers of occupational health, Irving Selikoff, once said that “statistics are people with the tears wiped away.”

Today, the statistics look bad. This week we learned that coal mining deaths doubled in 2017, and rose to their highest point in three years. Fifteen miners died on the job in 2017, compared with eight in 2016, according to the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA).

And a couple of weeks ago, we learned that in 2016, overall deaths in the workplace rose 7% over the year before, the third annual increase in a row. 5,190 fatal work injuries died on the job in 2016, 14 workers every day. We won’t know for almost a year how many non-coal mining workers died on the job in 2017.

Putting the Tears Back

But as Selikoff said, those are just numbers. This week, as I was compiling the Weekly Toll I ran across a few stories that should put some tears back in those numbers.

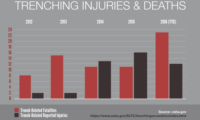

Buried Alive: Anyone who reads Confined Space on a regular basis knows that almost nothing makes me more angry than seeing workers buried alive in an unprotected trench. If you want to know more about the impact of such deaths, make sure you check out Jim Morris’s investigative piece last month, Death in a Trench.

Two workers died in trench collapses over the past couple of weeks. Zachary Hess died in a trench collapse in Warren County, Ohio, and Jesse Foster was killed in a trench collapse in Bell Aire, Kansas. Both are tragedies, but Hess’s death stands out. An estimated 150 people from rescue squads from around the area rushed to the scene in a vain attempt to rescue Hess. Despite firefighters clawing at the earth with their bare hands to get him out, the effort was hopeless. Hess was buried under tons of soil, 20 feet to 30 feet down. It took over 24 hours to recover the body.

What was especially infuriating about this death is that Hess’s employer, JK Excavating & Utilities of Mason, Ohio, was cited by OSHA just over three years ago for violations of OSHA’s trenching standard. The company received a $13,300 penalty, later reduced to $5,850. Somehow, the message that trenches over 5 feet deep have to be protected didn’t sink in as the company sent Zachary Hess to his death in a 20-30 foot, unprotected trench.

Machinery Rips Off Worker’s Leg: Domingo Alonzo Ramos was killed when his leg was ripped off after his foot got trapped in an auger used to grind meat scraps for garbage. “He screamed, and the other employees were able to stop the machine,” according to Rick Walters, investigator for the Stark County Coroner. They weren’t able to free him, however, and Ramos bled to death, Walters said. Ramos, a Guatemalan native, was undocumented and had worked at Fresh Mark, a meat processing facility, under an assumed name for over a year. In 2011, a worker at Fresh Mark’s Canton plant was electrocuted when he tried to plug in a fan while standing in water, according to OSHA, and the facility has received numerous OSHA citations over past several years for machine guarding and other violations.

And in case you think that deaths like this — cleaning up meat processing plants — are rare, check out Peter Waldman and Kartikay Mehrotra’s disturbing article last week “America’s Worst Graveyard Shift Is Grinding Up Workers.”

Boiled to Death: 28–year-old Frankie Crispin, Jr., a journeyman electrician at Columbia Forest Products in Klamath Falls, Oregon, was “found dead in a vat of scalding hot corrosive liquid. It appeared he fell through the lid of the vat, which sits a few feet above the ground.”

As the Oregonian described:

Are There Lessons To Be Learned?

I don’t have any good explanation about why fatalities are trending up — both in general industry and in coal mining. We could blame the increase in mining deaths on a message sent out to the industry that the Trump Administration will do anything (or overlook anything) to promote the mining industry. Of course that doesn’t explain the rise in 2016 deaths that occurred under the Obama administration.

All of these cases are in the early stages of investigation, but there are some lessons we can pull from these deaths.

Neither OSHA nor MSHA have received a budget increase since 2010 and, in fact, their budget have gone down in both real and inflation-adjusted terms. For OSHA, that has meant fewer enforcement staff every year, and fewer inspections. Add that to Trump’s hiring freeze, and as I wrote earlier, the agency’s enforcement and whistleblower programs are “falling apart at the seams,” according to OSHA staff.

All of the employers above had received previous OSHA citations, for Fresh Mark and JK Excavating, apparently for the exact hazards that killed their employees. Columbia Forest Products has also received past OSHA citations, although nothing major stands our for “America’s largest manufacturer of hardwood plywood and hardwood veneer products.”

I don’t know any more details of these deaths than I’ve read in the paper, but judging from the fact that Fresh Mark and JK Excavating were clearly aware of the hazards, I would hope they will receive willful citations –and with that the possibility of criminal prosecution.

We also know that none of the employers are union, which means that if the workers were worried about hazards in the workplace, they were likely afraid to bring them up to their employers or call OSHA (assuming they even knew what OSHA was.) And that goes doubly for Ramos who was undocumented and already under threat of deportation. Being represented by a union, is, of course, no guarantee that the employer will comply with the law, but it does raise the odds that workers will be knowledgeable about the hazards they face and able to exercise their rights with less fear of retaliation.

What Is To be Done? Turning Tears Into Action

So knowing what we know, what can we prescribe to make sure these deaths don’t happen again.

- Budget: Clearly OSHA and MSHA need significant budget increases. Enforcement and whistleblower programs need to be significantly increased so that there is a credible threat that an inspector will appear in any workplace at any time, and that employers who retaliate against workers will be sanctioned in a reasonable amount of time.

- Enforcement: OSHA, MSHA and Department of Labor leadership needs to send a strong message out — in word and in deed — that they will strongly enforce the law, including pursing criminal prosecutions. The Administration should also back legislation that would improve OSHA’s ability to pursue criminal prosecution and improve its weak whistleblower language.

- Compliance Assistance: OSHA’s compliance assistance dollars need to be focused on vulnerable workers who don’t have access to information about the hazards they face or their rights, and to small employers who may not have the resources to hire full-time health and safety staff and consultants.

Undocumented workers need to understand that OSHA does not care about employment or immigration status when it comes to enforcing safe workplaces. This means increasing (and not eliminating) the Susan Harwood Training Grant Program that can provide training for workers that OSHA is otherwise unable to reach. Programs like the Voluntary Protection Programs (VPP) should continue to highlight those employers who exceed OSHA standards, but they should not be a drain on OSHA’s enforcement program.

- Unions: As I said above, workers in worksites with unions are more likely to be educated about their rights and the hazards they face, and are more likely to be able to use those rights to get employers to make their workplaces safer. Laws that make it easier for unions to organize and harder for anti-union employers to illegally oppose unions need to be strengthened.

And unions themselves, although struggling, should be putting more resources, not fewer, into the health and safety of their members. Although it’s sometimes hard to understand at union headquarters, but members want and need the union’s assistance and support to ensure that they will come home in one piece at the end of the shift.

It’s the beginning of the year. Time to make plans and resolutions. Even in government agencies. So if anyone at OSHA or MSHA Is reading this, please forward a copy down to the Assistance Secretary’s office. I’m sure they’ll thank you for it.

Click here to visit Confined Space.