Statement of David Michaels, Ph.D, MPH, Assistant Secretary, OSHA before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Education and the Workforce, Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, Oct. 5:

Thank you very much for inviting me to testify here today. I appreciate the opportunity to come before you to describe the important work of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and to listen to your comments and suggestions about how we can best fulfill the important mission given to us by the Congress to protect America's workers while on the job.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the establishment of OSHA and I think by any measure, this agency has been one of the true successes of government efforts to protect workers and promote the public welfare.

It is difficult to believe that only 40 years ago most American workers did not enjoy the basic human right to work in a safe workplace. Instead, they were told they had a choice: They could continue to work under dangerous conditions, risking their lives, or they could move on to another job. Passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act) laid the foundation for the great progress we have made in worker safety and health since those days.

The promise of a safe and healthful workplace is as important today as it was 40 years ago when the OSH Act first passed. We understand and share your concern and the concern of all Americans that protecting workers' health and lives on the job not interfere with the efforts we are making to ensure that businesses and jobs in this country grow and thrive on a level playing field. But neither should we let an economic crisis leave workers more at risk. As the President recently reminded us in his address to the Joint Session of Congress:

"what we can't do . . . is let this economic crisis be used as an excuse to wipe out the basic protections that Americans have counted on for decades. I reject the idea that we need to ask people to choose between their jobs and their safety."

OSHA has proven over the past 40 years that we can have both jobs and job safety. Employers, unions, academia, and private safety and health organizations pay a great deal more attention to worker protection today than they did prior to enactment of this landmark legislation. Indeed, the results of this law speak for themselves. In 1971, the National Safety Council estimated that 38 workers died on the job every day of the year. Today, the number is 12 per day, with a workforce that is almost twice as large. Injuries and illnesses also are down dramatically — from 10.9 per 100 workers per year in 1972 to less than 4 per 100 workers in 2009.

Some of this decline in injuries, illnesses and fatalities is due to the shift of our economy from manufacturing to service industries. However, it is also clear that much of this progress can be attributed to improved employer safety and health practices encouraged by the existence of a government regulatory agency focused on identifying and eliminating workplace hazards and assisting employers in implementing the best practices to eliminate those hazards.

The evidence is unambiguous – OSHA's common sense standards save lives:

In the late 1980s, OSHA enacted a standard to protect workers in grain handling facilities from dust explosions. Since then, explosions in these industries have declined 42 percent, worker injuries have dropped 60 percent, and worker deaths have fallen 70 percent.

OSHA's 1978 Cotton Dust standard drove down rates of brown lung disease among textile workers from 12 percent to 1 percent.

OSHA efforts in promulgating the asbestos and benzene standards are responsible for dramatic reductions in workplace exposure to asbestos, a mineral that causes asbestosis, lung cancer and mesothelioma (a cancer of the lining of the lungs and stomach) and to benzene, a solvent that causes leukemia. These two standards alone have prevented many thousands of cases of cancer.

OSHA standards have helped shield healthcare workers from needlestick hazards and bloodborne pathogens. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, new cases of workplace-acquired Hepatitis B among healthcare workers decreased 95%, as a result of the widespread hepatitis B immunization and the use of universal precautions and other measures required by OSHA's bloodborne pathogens standard.1

Although these are notable successes, there is still much work to do. Every week I sign a stack of letters, telling the mother, or husband, or child of a worker killed on the job that OSHA is opening an investigation into the events that led to the death of their loved one.

Each of the twelve workers who die on the job every single day in this country could well leave behind grieving children, spouses and parents. Unfortunately, most of these fatalities never make the national headlines or even the front pages of local papers.

And these 12 workers killed on the job today and every day do not account for the tens of thousands of workers estimated to die every year from work-related disease.

Too often overlooked are the over 3 million workers who are seriously injured each year. Far too many of these injuries end up destroying a family's middle class security.

Workplace injuries, illnesses and fatalities take an enormous toll on this nation's economy – a toll that is barely affordable in good times, but is intolerable in difficult economic times such as we are experiencing today. A March 2010 Liberty Mutual Insurance company report showed that the most disabling injuries (those involving 6 or more days away from work) cost American employers more than $53 billion a year – over $1 billion a week – in workers' compensation costs alone. Indirect costs to employers, such as costs of down time for other employees as a result of the accident, investigations, claims adjustment, legal fees, and associated property damage can be up to double these costs. Costs to employees and their families through wage losses uncompensated by workers' compensation, household responsibilities, and family care for the workers further increase the total costs to the economy, even without considering pain and suffering.2

We recently saw the real economic impact of neglecting job safety when Con Agra announced that it would close down the Slim Jim plant in Garner, North Carolina after a violent gas explosion in the plant killed four workers. Not only did four workers never come home that day, but now their community is devastated with over 400 employees laid off.

Almost the same thing happened in Jacksonville Florida a few years ago. Just before the 2007 holiday season, a similar explosion at T2 Laboratories killed four workers and hospitalized 14. The explosion's force was equivalent to detonating about a ton of TNT and it spread debris up to a mile from the plant. The blaze required every hazardous material unit in Jacksonville and over 100 firefighters to respond. In the following months, T2 permanently shut down its facilities, and laid off all the workers.

Clearly it's not only good business to prevent workplace injuries and illnesses, but the small amount of money that goes to fund this agency is a worthwhile investment for the general welfare of the American people.

I want to review with you briefly how OSHA approaches these challenges.

Deterrence Through Fair Enforcement

The primary purpose of OSHA's enforcement program is deterrence. OSHA's enforcement program specifically targets the most dangerous workplaces and the most recalcitrant employers. We recognize that most employers want to keep their employees safe and make great efforts to protect them from workplace hazards. We are committed to being good stewards of the taxpayers' funds entrusted to us by using our resources as efficiently and effectively as possible to protect those workers most at risk.

Strong and fair enforcement of the law has particular importance during this difficult economic period. In the short term, responsible employers who invest in the health and safety of their employees are at a disadvantage competing with irresponsible employers who cut corners on worker protection and hazard abatement. Strong and fair enforcement, accompanied by meaningful penalties, levels the playing field.

Let me give you a current example. Just last week a reporter called to relate a conversation he had just had with a very unhappy small residential building contractor who complained that while he readily provided fall protection to ensure the safety of his employees, many of his competitors did not, giving them an unfair advantage when bidding contracts. How was that fair?

Well the fact is, it wasn't fair. He was right. Falls are the number one cause of fatalities in construction, killing almost 1900 workers from 2005-2009 and injuring thousands. And 548 of these fatalities occurred in residential construction. Yet some residential construction operations (for example, on less steep roofs) had received a temporary exemption in 1995 while a few remaining feasibility issues were resolved. (Note that many states, including California and Washington, never adopted our exemption, and have required residential construction to protect workers with fall protection since 1994.) Seventeen years later, those issues have been resolved and OSHA received requests from business -- including the National Association of Home Builders, the organization representing 22 state OSHA programs and labor organizations -- to remove the confusing exemption. So last December, OSHA announced that it would fully enforce its 1994 fall protection standard for all residential construction operations.

And, by issuing our new residential fall protection policy, OSHA leveled the playing field for that unhappy small employer and for thousands of other responsible contractors who are trying to compete with those who are trying to cut corners and costs on worker safety.

Over the longer term, of course, safety pays: good safety and health management tends to translate into profitability and a stronger national economy by preventing worker injuries, saving on a host of costs, spurring worker engagement, and enhancing the company's reputation.

The core purpose of OSHA's enforcement program is prevention, not punishment. Just as it makes sense for the police to pull over a drunk driver before he causes death or injury, it is OSHA's objective to encourage employers to abate hazards before workers are hurt or killed, rather than afterwards, when it's too late. In fact, 97% of OSHA's citations are issued without a worker being killed or injured first. This is the essence of prevention.

The fact is that OSHA saves lives. It is sometimes difficult to illustrate individual cases of where OSHA enforcement has saved a life because, in general, it is statistics that show that injuries have been prevented and that lives have been saved by our efforts. In general, we cannot identify the particular life saved or the tragic accident that never happened because of hazard abatement.

But occasionally a series of events occurs in which the time between the hazard abatement and injury prevented is so short, and the relationship so obvious, that the impact of OSHA enforcement is illuminated.

Just a few weeks ago, OSHA cited a small residential construction employer, German Terrazas, for not using fall protection. He got the message, purchased fall protection equipment and signed up for an OSHA safety class. Two weeks later, German Terrazas himself fell while working on a residential roof – but he didn't fall to the ground and he didn't fall to his death. The fall restraint equipment that he purchased and used after the OSHA citation very likely saved his life.

Another such series of events occurred earlier this year, in Mercerville, Ohio. Our inspectors were called to investigate a report of a worker in a deep construction trench. Upon arrival, OSHA inspector Rick Burns identified a worker in a 10-foot deep unprotected trench. OSHA regulations require trenches greater than 5 feet deep to be shored, sloped or protected in some way.

Burns immediately directed the worker to leave the trench. The worker exited the trench and five minutes later, the walls of the trench collapsed right where the worker had been standing. There is little doubt that he would have been seriously injured or killed absent the intervention of the OSHA inspector.

These two photographs, taken only minutes apart at this site, illustrate the value of OSHA enforcement.

These two photographs, taken only minutes apart at this site, illustrate the value of OSHA enforcement.

This may seem like a rare series of events, but a similar sequence occurred a few short weeks later in Auburn, Alabama. OSHA inspectors ordered workers out of a trench minutes before it collapsed. A photograph taken minutes later is below; before they exited the trench, the workers had been situated just below the excavator in the photo.

Unfortunately, it doesn't always end this way. Last year, for example, OSHA fined a Butler County, PA construction company $539,000 following the investigation of the death of Carl Beck Jr., a roofing worker who fell 40 feet at a Washington, PA worksite. Fall protection equipment was available on site but Christopher Franc, the contractor, did not require his workers to use it. Mr. Beck was 29 years old and is survived by his wife and two small children. Mr. Franc entered a guilty plea in federal court to a criminal violation of the Occupational Safety and Health Act and was sentenced to three years probation, six months home detention, and payment of funeral expenses on his conviction of a willful violation of an OSHA regulation causing the death of an employee.

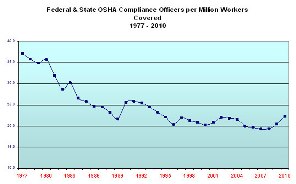

Federal OSHA and the 27 OSHA state plans together have approximately 2,200 inspectors charged with protecting more than 130 million workers in more than 8 million workplaces across the country. And the ratio of OSHA compliance officers to covered workers has fallen substantially over the past three decades. In 1977, for example, OSHA had 37 inspectors for every million covered workers, while today OSHA has just over 22 inspectors for every million covered workers.

OSHA conducts inspections of those workplaces where there has been a fatality, multiple hospitalizations, where a worker files a formal complaint or where there is an imminent danger of a worker's death. Beyond those inspections, we have put great thought and strategic planning into prioritizing the rest of our enforcement program in order to ensure that we are being as efficient and effective as possible. For example, through our Site Specific Targeting Program, OSHA focuses on those employers with the most injuries and illnesses in their workplaces. OSHA also has a variety of National Emphasis Programs (NEPs) and Local Emphasis Programs (LEPs) that target major hazards or hazardous industries. For example, following the British Petroleum (BP) Texas City explosion that killed 15 workers in 2005, OSHA implemented an NEP to inspect this nation's refineries. We have NEPs for combustible dust and LEPs focusing on grain engulfments where we've seen a large number of fatalities, many of which were of very young workers, over the past year.

OSHA's Severe Violator Enforcement Program (SVEP) is another example of our strategic investments in enforcement. SVEP concentrates resources on inspecting employers who have demonstrated indifference to their OSH Act obligations by committing willful, repeated, or failure-to-abate violations.

SVEP is intended to ensure that OSHA is more able to efficiently identify and focus our resources on the most recalcitrant employers who disregard the law and endanger the lives of their employees.

OSHA Penalties

OSHA proposes penalties to employers when we find hazards that threaten the health and safety of workers. As discussed earlier, the purpose of the penalties is deterrence. OSHA penalties are set by law. Maximum OSHA penalty amounts have been unchanged since 1990. The maximum penalty for a serious violation remains at $7000. OSHA is statutorily mandated to take into account a business's size, history and evidence of good faith when calculating a penalty. Moreover, OSHA penalties do not rise with inflation, which means that the real dollar value of OSHA penalties has been reduced by 39% since 1998.

For example, last year a 47 year-old roofing employee, with seven years experience, stepped off the back of a roof and fell 15 feet onto a concrete slab below. He died two days later. He had not been provided fall protection. The total proposed penalty for his employer was only $4,200 for not providing fall protection. After the incident, the employer provided fall protection equipment including harnesses, lanyards and roof anchors to employees.

While OSHA recently modified its administrative penalty policy reduction factors to provide a modest increase in average penalties, the average OSHA penalty remains very low. In 2010, OSHA's average penalty for a serious violation (capable of causing death or serious physical harm), was only $1,000 and for small employers, only $763. Right now the average penalty for all employers is closer to $2,000, still low, but an improvement. OSHA continues to closely monitor the effect of our penalties on small businesses.

While OSHA is working within the parameters set in existing law, the Administration continues to support the Protecting America's Workers Act in order to give OSHA the tools to impose appropriate penalties to increase deterrence and save lives. OSHA must be empowered to send a stronger message in the most egregious cases.

Compliance Assistance: Help for Small Businesses and Vulnerable Workers

The second major component of OSHA's strategy is compliance assistance, which includes outreach, consultation, training, grant programs and cooperative programs. Our commitment to compliance assistance is strong and growing.

There are several principles under which our compliance assistance program operates:

-

We believe that no employer, large or small, should fail to provide a safe workplace simply because it can't get accurate and timely information about how to address workplace safety or health problems or how to implement OSHA standards.

-

All workers, no matter what language they speak or who their employer is, should be knowledgeable about the hazards they face, the protections they need and their rights under the OSH Act.

-

Employers that achieve excellence in their health and safety programs should receive recognition.

Too many workers still do not understand their rights under the law or are too intimidated to exercise those rights. Too many workers and employers still do not have basic information about workplace hazards and what to do about them. And too many employers still find it far too easy to cut corners on safety, and even when cited, consider low OSHA penalties to be just an acceptable cost of doing business.

OSHA's primary compliance assistance program is its On-site Consultation Program. We understand that most small businesses want to protect their employees, but often cannot afford to hire a health and safety professional. This help for small businesses is critical both for the health of these businesses and for the safety and health of the millions of workers employed by small businesses. OSHA's data shows that 70% of all fatality cases investigated by the Agency occur in businesses that employ 50 or fewer employees. Our compliance assistance focus on small businesses is good for the economy and for workers.

OSHA's On-site Consultation Program is designed to provide professional, high-quality, individualized assistance to small businesses at no cost. This service provides free and confidential workplace safety and health evaluations and advice to small businesses with 250 or fewer employees, and is separate and independent from OSHA's enforcement program. Last year, the On-Site Consultation Program conducted over 30,000 visits to small businesses.

In these difficult budgetary times, the high priority that we put on this support for small businesses is manifest in the President's budget requests. In FY 2011, the President requested a $1 million increase in this program, and this request was repeated in the FY 2012 budget.

In addition, OSHA has over 70 compliance assistance specialists located in OSHA's area offices who are dedicated to assisting employers and workers in understanding hazards and how to control them. Last year alone, this staff conducted almost 7,000 outreach activities reaching employers and workers across the country.

OSHA continues its strong support for recognizing and holding up those employers who "get safety". We continue to support OSHA's landmark Voluntary Protection Program. For small employers, the OSHA On-site Consultation Programs Safety and Health Achievement Recognition Program or SHARP, also recognizes small businesses that have achieved excellence. In order to participate in these programs, employers commit to implement model injury and illness prevention programs that go far beyond OSHA's requirements. These employers demonstrate that "safety pays" and serve as a model to all businesses.

The experience that ALMACO, a manufacturing company in Iowa, had through working with On-site Consultation and being recognized in SHARP is a good example of the positive impact these programs have on workplace safety and health. Prior to working with the Iowa Bureau of Consultation and Education (Iowa Consultation) ALMACO's injury and illness rate was over three times the national average for companies in its industry. By 2010 approximately 10 years after initiating a relationship with Iowa consultation, ALMACO had lowered its incident rate to less than half the industry average. Further, since 2005, it has experienced a 37% reduction in its workers compensation insurance employer modification rate, and a 79% reduction in its employee turnover rate.

For the vast majority of employers who want to do the right thing, we want to put the right tools in their hands to maintain a safe and healthful workplace. That is why we invest in our compliance assistance materials and why our website is so popular. New OSHA standards and enforcement initiatives are always accompanied by web pages, fact sheets, guidance documents, on-line webinars, interactive training programs and special products for small businesses. In addition, our compliance assistance specialists supplement this with a robust outreach and education program for employers and workers.

A major new initiative of this administration has been increased outreach to hard-to-reach vulnerable workers, including those who have limited English proficiency. These employees are often employed in the most hazardous jobs, and may not have the same employer from one week to the next.

We have particularly focused on Latino workers. Among the most vulnerable workers in America are those who work in high-risk industries, particularly construction. Latino workers suffer higher work related fatality and injury rates on the job because they are often in the most dangerous jobs and do not receive proper training.

Another critical piece of our strategic effort to prevent workplace fatalities, injuries and illnesses is training workers about job hazards and protections. OSHA's Susan Harwood Training grant program provides funding for valuable training and technical assistance to non-profit organizations – employer associations, universities, community colleges, unions, and community and faith based organizations. This program focuses on providing training to workers in high risk industries and is also increasing its focus on organizations involved in training vulnerable, limited English speaking and other hard-to-reach workers to assure they receive the training they need to be safe and healthy in the workplace. For example, just last week, Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana was awarded a Susan Harwood grant to provide training to farm owners, farm operators, and farm workers (including youth) on safety and health hazards related to grain storage and handling. This training is critical as we have seen a recent increase in grain engulfment fatalities. Tragically, several of these incidents have involved teenagers. We are pleased that business associations, unions and community groups have joined us in this effort.

Whistleblower Protection

The creators of the OSH Act understood that OSHA inspectors would not be able to be at every workplace every day, so the Act was constructed to encourage worker participation and to rely heavily on workers to act as OSHA's "eyes and ears" in identifying hazards at their workplaces. If employees fear that they will lose their jobs or be otherwise retaliated against for actively participating in safety and health activities, they are not likely to do so. Achieving the Secretary of Labor's goal of "Good Jobs for Everyone" includes strengthening workers' voices in their workplaces. Without robust job protections, these voices may be silenced.

It is notable that since the OSH Act was passed in 1970, Congress has passed, and added to OSHA's enforcement responsibilities, 20 additional whistleblower laws to protect employees who report violations of various trucking, airline, nuclear power, pipeline, environmental, rail, mass transit, maritime safety, consumer product safety, and securities laws. In just the past year, four additional whistleblower laws were added to OSHA's enforcement responsibilities. Despite this increase in OSHA's statutory load, the staff charged with enforcing those laws did not grow significantly until FY 2010 when 25 whistleblower investigators were authorized. In just the past year, however, four additional whistleblower laws were added to OSHA's enforcement responsibility. These new responsibilities are stretching OSHA's whistleblower resources to the breaking point. We are committed to doing the most that we can with our strained whistleblower resources. That is why I directed a top-to-bottom review of the program to ensure that we are as efficient and effective as possible and that we address the criticism of the whistleblower program raised in reports by the Government Accountability Office and the Department's Inspector General. We are happy to report to you that OSHA has made great strides in improving the performance of this critical program.

As a result, we will be moving our whistleblower protection program from our Directorate of Enforcement Programs, to report directly to my office. We are also considering several reorganization plans in the field. We have recently revised the whistleblower protection manual. Just two weeks ago, we conducted a national whistleblower conference that included whistleblower investigators from federal as well as state plan states, along with regional and national office attorneys who work on this issue.

Regulatory Process and the Costs of Regulation

OSHA's mission is to ensure that everyone who goes to work is able to return home safely at the end of their shift. One of the primary means Congress has given to OSHA to accomplish this task is to issue common sense standards and regulations to protect workers from workplace hazards. OSHA's common sense standards have made working conditions in America today far safer than 40 years ago when the agency was created, without slowing the growth of American business.

Developing OSHA regulations is a complex process that often involves sophisticated risk assessments as well as detailed economic and technological feasibility analyses. These complicated analyses are critical to ensuring that OSHA's regulations effectively protect workers and at the same time make sense for the regulated community that will be charged with implementing the regulations.

The regulatory process also includes multiple points where the agency receives comments from stakeholders such as large and small businesses, professional organizations, trade associations as well as workers and labor representatives. OSHA issues very few standards and all are the product of years of careful work and consultation with all stakeholders. Over the past 15 years, OSHA has, on average, issued only a few major standards each year, with some periods in which no major standards have been issued.

In fact, over the past year, OSHA has issued only two major standards: one protecting workers from hazards associated with cranes and derricks, and another standard to protect shipyard workers. Both took years to develop. Implementation of these standards is proceeding very smoothly with great cooperation from workers and the regulated communities.

Our commitment to the Administration's initiative to ensure smart regulations is already evident. OSHA recently announced a final rule that will remove over 1.9 million annual hours of paperwork burdens on employers and save more than $40 million in annual costs. Businesses will no longer be saddled with the obligation to fill out unnecessary government forms, meaning that their employees will have more time to be productive and do their real work.

One of the next standards that OSHA will issue is a revision of our Hazard Communication Standard to align with the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals. Aligning OSHA's Hazard Communication Standard with the GHS will not only improve chemical hazard information provided to workers, but also make it much easier for American chemical manufacturers to sell their products around the world. In addition, over time, employers, especially in small businesses, will find it easier to train their employees using a uniform system of labeling, saving them both time and money.

I am confident that our lengthy, careful and methodical regulatory process, with its robust opportunities for stakeholder input and comment, will produce a common sense and successful Injury and Illness Prevention Program proposal and standard. I have this confidence because that is what the history of OSHA's regulatory process demonstrates. This Subcommittee and our regulated community should look to our past to see how OSHA standards can enhance American economic competitiveness, not hinder it. OSHA standards don't just prevent worker injuries and illnesses, but they also drive technological innovation, making industries more competitive.

In fact, there is also clear evidence that both regulated industries and the agency itself generally overestimate the cost of new OSHA standards. Congress' Office of Technology Assessment (OTA), comparing the predicted and actual costs of eight OSHA regulations, found that in almost all cases, "industries that were most affected achieved compliance straightforwardly, and largely avoided the destructive economic effects" that they had predicted.3

For example:

-

In 1974, OSHA issued a regulation to reduce worker exposure to vinyl chloride, a chemical used in making plastic for hundreds of products. Vinyl Chloride was proven to cause a rare liver cancer among exposed workers. Plastics manufacturers told OSHA that a new standard would kill as many as 2.2 million jobs. 4 Two years after the 1974 vinyl chloride regulation went into effect, Chemical Week described manufacturers rushing to "improve existing operations and build new units" to meet increased market demand.5 The Congressional study looked at the data and confirmed not only that the vinyl industry spent only a quarter of OSHA's original estimate to comply with the standard, but that the new technology designed to meet the standard actually increased productivity.

-

In 1984, OSHA implemented its ethylene oxide standard to reduce workers' exposure to this cancer-causing gas used for sterilizing equipment in hospitals and other health care facilities. OSHA's new rule required employers to ventilate work areas and monitor workers' exposure levels — changes predicted to add modest costs while ensuring enormous protections for workers. Complying with the ethylene oxide rule also led U.S. equipment manufacturers to produce innovative technology and hasten hospital modernization.

We have heard from many employer groups and labor organizations, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the American Chemistry Council, that OSHA must update its chemical Permissible Exposure Limits (PELs). These are standards adopted at OSHA's birth, many of which are based on science from the 1950's and 1960's, and do not reflect updated scientific research on cancer and other chronic health effects. I would like to join hands with business and labor and tackle this project, but our complicated regulatory process makes progress difficult. I would like to work with this Subcommittee, as well as the regulated community, to find creative ways to address the PELs challenge.

Outreach to Stakeholders

One of the most important parts of the regulatory process is OSHA's extensive consultation with all affected parties, including large and small business, workers and labor organizations and professional workplace safety associations. Although the Occupational Safety and Health Act, the Administrative Procedures Act, and other laws such as the Regulatory Flexibility Act, as amended by the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA) require a certain level of public input, OSHA routinely goes above and beyond these requirements.

We enthusiastically welcome public input. OSHA's first priority is to issue standards that protect workers. But it makes absolutely no sense to issue standards that don't work or that don't make sense to businesses and workers in a real workplace. Getting input from workers and businesses, based on their experience, about what works and what doesn't work is not only essential to issuing good, common sense rules, but also welcomed by this agency.

Our efforts are consistent with the Administration's commitment in E.O. 13563 to have as transparent and inclusive a regulatory process as possible. I began this commitment even prior to the issuance of the Executive Order. The genesis of our current regulatory agenda is the extensive public outreach I did when I first came on the job. In fact, one of the first actions I implemented when becoming Assistant Secretary was to hold an all day stakeholder event, OSHA Listens, to obtain information from the public on key issues facing the agency. We heard from small and large businesses, trade associations, unions and workers, victims' families, advocacy organizations and safety and health professionals. We learned a lot from this session and many of our Regions are holding similar sessions. We will continue all of these outreach efforts and add more as appropriate.

OSHA has continued to go far beyond the required steps of the rulemaking process. Beyond the comment periods and hearings required by law, OSHA generally adds a number of other options to receive public input including stakeholder meetings and webchats. In addition, OSHA leadership and OSHA technical experts travel to numerous meetings of business associations, unions and public health organizations to discuss our regulatory activities and gather input. For example, OSHA has held five stakeholder meetings around the country on its Injury and Illness Prevention Programs initiative. OSHA has also held three stakeholder meetings, including its first ever virtual stakeholder meeting by a webinar, and convened an expert panel on a potential combustible dust standard. OSHA held a stakeholder meeting on a potential infectious disease standard and regularly holds webinars on its regulatory agenda. We have also done public outreach on better ways to protect workers against hearing loss and we are planning a stakeholder meeting on this subject next month.

OSHA also uses a variety of other mechanisms such as its four formal advisory committees and various informal meetings with groups such as its Alliance Program Construction Roundtable meetings to constantly seek input from labor and industry on a variety of safety and health issues.

Conclusion

Our nation has a long history of treating workplace safety as a bipartisan issue. The OSH Act was the product of a bipartisan compromise. It was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 29, 1970, who called it "probably one of the most important pieces of legislation, from the standpoint of the 55 million people who will be covered by it ever passed by the Congress of the United States, because it involves their lives." Bearing witness at that bill signing were both Democratic and Republican Congressional leaders, as well as the Presidents of the National Association of Manufacturers and the Chamber of Commerce and labor leaders.

Now covering 107 million workers, the Act is no less important today, 40 years later. I am very excited about the initiatives that this Administration has taken to fulfill the goals of this law and to protect our most valuable national resource – our workers.

I want to thank you again for inviting me to this hearing to describe to you the efforts we are taking to protect American workers and to get your input about how we can do this even more effectively. I look forward to your questions at this hearing and I am also willing to come to meet with you or your staff personally to discuss any of our initiatives in more detail.

1 http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2000-108/pdfs/2000-108.pdf*

2 Liberty Mutual Research Institute for Safety, 2010 Liberty Mutual Workplace Safety Index, available at http://www.libertymutualgroup.com/omapps/ContentServer?c=cms_document&pagename=LMGResearchInstitute/cms_document/ShowDoc&cid=1138365240689*.

3 Office of Technology Assessment, Gauging Control Technology and Regulatory Impacts in Occupational Safety and Health: An Appraisal of OSHA's Analytic Approach September 1995.

4 Brody, J Vinyl Chloride Exposure Limit Is Opposed by Plastics Industry. New York Times June 6, 1974,

5 PVC rolls out of jeopardy, into jubilation. Chemical Week. September 15, 1976:34.