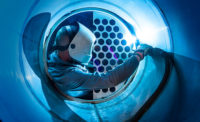

A permit-required confined space has the potential to present inherent risks to worker health and safety and should be entered only when necessary and always with extreme caution. Unfortunately, there are times when employers will need to authorize their employees to enter these work areas for either planned maintenance or for emergency repairs. After carefully considering whether entry is, in fact, necessary, the decision-maker's job is to select a rescue service capable of providing timely/effective response during confined space entry.

The on-site assessment: Is entry rescue necessary?

The employer’s first obligation regarding rescue is to determine whether non-entry rescue is feasible and to ensure that it would not create a greater hazard than what is already present.

Non-entry rescue should be the first option if – and only if – the non-entry retrieval system has a very strong likelihood of performing effectively in every instance. This requires an honest on-site assessment of what could possibly go wrong. (Author’s note: Murphy’s Law is a serious consideration when it comes to non-entry rescue systems: If there is a chance something could go wrong, it most likely will).

When determining the feasibility of non-entry rescue, you should evaluate the following:

- Is there any chance that the retrieval line may become entangled?

- Are there any obstructions on the floor that would impede a horizontal retrieval?

- If the entrant were to become disoriented or rendered unconscious, could they move to or fall into a position from which the retrieval system would have difficulty freeing them?

These questions must be answered before committing to a non-entry rescue retrieval system.

If non-entry rescue is not an option, you must select and evaluate a competent rescue service. This rescue service or rescue team can be one of three primary groups: in-house employees, municipal responders, and contracted third-party rescue teams. There are advantages and disadvantages to all three options, and there are also some common factors that employers must consider when deciding which service to rely on.

In-house rescue teams: home-field advantage?

In-house rescue teams made up of host employees may be comprised of either a dedicated unit such as an onsite fire company or emergency response team (ERT) or may be made up of employees that are part of the rescue team as a secondary duty. The advantage of having a rescue team comprised of host employees is that they have a really good understanding of the layout of the facility, know the potential hazards, and typically have the shortest response time when not on a rescue standby posture.

In my experience, the main disadvantage of in-house rescue teams is they do not have access to the same quantity and quality of proficiency training as professional dedicated rescue teams. Although this is not universally true, rescue teams made up of host employees can often lack sufficient training, especially if they are not members of a dedicated fire company or full-time ERT.

Municipal responders: a duty to the public first?

Municipal responders such as local fire departments are another option to consider. The benefit of this option is that it incurs no expense to the employer in terms of payroll, training costs, or the expense of purchasing and maintaining rescue equipment provided the department is properly outfitted and trained for confined space rescue. (Author’s note: For this reason, some businesses reciprocate by providing funding to the local fire department for rescue equipment or training).

Some disadvantages to relying on municipal responders include delayed response time, less familiarity with the layout of the site, the possible need for access and escort, and perhaps a lesser awareness of the hazards associated with the spaces.

But one key disadvantage that is often overlooked is the ability and willingness of the fire department to notify the employer to suspend entry operations if they are not available to respond. It is rare that a municipal dispatch station would notify the private sector employers in the event the fire department rescue team is called to an emergency such as vehicle extrication or another technical rescue event.

Third-party rescue services: Costly but cost-effective

Third party professional contracted rescue services are the third option to consider for your confined space entry rescue needs. The obvious disadvantage of this option is the cost. But if you perform entries that require entry rescue infrequently, or you need all host employee hands on deck during a turnaround, then this may actually be more cost-effective than training and equipping an in-house team or pulling them off of their primary job during a turnaround.

Most contracted rescue teams maintain a very high standard of proficiency. You should expect them to prepare comprehensive rescue preplans for any and all relevant spaces. Of course, they should also be prepared to provide appropriate PPE and monitoring equipment for their rescuers based on the hazards of the spaces.

No matter which of the three options you choose for confined space entry rescue, capability evaluations are critically important to ensuring that you will have an asset that you can rely on if things go wrong.

OSHA 1910.146 Appendix F provides a clear road map to selecting and evaluating a prospective confined space rescue service. Appendix F is broken down into two distinct phases: (1) an initial evaluation which we like to refer to as the “can they talk the talk” phase; and, (2) a follow-on performance evaluation where you learn if they can “walk the walk.”

Two-phase evaluation

The initial evaluation should determine if the rescue service is trained and equipped to perform the types of rescue you may require at your facility. The next question is to determine if they can respond in a time that is appropriate for the types of hazards that are known or potentially present that may affect entrants in those spaces. The initial evaluation asks ten simple questions that get right to the heart of timely response, communications, patient evaluation and packaging, and the ability to perform a rescue from certain space configurations.

The second phase of the evaluation is to demonstrate proficiency in the types of rescues that teams may be called on to perform. This is known as the performance evaluation – and it’s really where the decision-maker can learn if the service can perform safely and effectively as a team. The performance evaluation calls for the service to practice at least once every twelve months or to have performed a successful rescue from a confined space in that timeframe.

Both general industry and construction industry regulations require the employer to make representative spaces available to the rescue service for planning purposes, which invites the first opportunity for the employer to assess the rescue team. Allow the team to visit your site and the spaces to determine if they have the skills and equipment to perform as required and to let them prepare rescue plans for each type of space.

Once that is done, and the prospective team has had a chance to close any training or equipment gaps, we suggest it is time to create a simulated rescue and evaluate their response. Place a mannequin or even a volunteer to act like the victim in a non-permit space of any configuration that is most common in your industry. Putting the team in a worst-case scenario will tell you a lot about the rescue team’s capabilities. Then schedule them to demonstrate the simulated rescue utilizing their rescue plan.

If you are not comfortable evaluating a prospective rescue team yourself, there are plenty of third-party experts available to provide an objective critique on your behalf.

The effort involved in completing the Appendix F performance evaluation is minimal compared to the potential failures of a poorly vetted rescue service. Consider the above criteria when choosing the ideal rescue support for your authorized confined space entrants.