Posted with permission from Fairwarning.org:

|

| Brown at recent garment workers union meeting in Dhaka, Bangladesh (Photo by Asiful Hoque) |

After decades of speaking out against workplace hazards in this country and abroad, Garrett Brown didn’t quietly fade away when he retired from his high-ranking state regulatory job in California. He came back to hound his former employer.

Brown released a blistering critique of the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health just weeks after leaving the agency at the end of last year. The report is the core of a watchdog group’s federal complaint trying to prod Cal/OSHA, as the agency is known, to add field inspectors and step up enforcement.

Then, in April, Brown lodged a whistleblower claim with the state auditor. In it he accuses the department that oversees Cal/OSHA of “improperly,” and “possibly illegally,” misusing money that is supposed to go to his former agency. And this month Brown launched a website, Inside Cal/OSHA, to step up his criticism of what he regards as the pro-employer drift of the agency.

Brown’s unconventional farewell after 20 years at Cal/OSHA, where he was a respected inspector before being named special assistant to the agency’s chief, was hardly out of character. Brown, 61, has been both a crusader and a buttoned-down career bureaucrat. After starting out as an activist, he came to the agency willing to work for change within the system. Yet over the years he riled his own bosses by publicly calling for more staff, arguing that the state has more fish and game wardens than job safety inspectors.

Long before arriving at Cal/OSHA, Brown was drawn to the plight of industrial workers. In his 20s, he did a stint as a newspaper reporter writing about steel mills in the Chicago area. Then Brown was a union factory laborer and forklift driver for four years — a period when he also was a member of the Socialist Worker Party and tried to organize workers around health and safety issues, before quitting the party in 1983. “It became clear that the Socialist Worker Party had an over-optimistic view that workers were on the verge of rebellion in the United States,” he said.

Brown, the son of a successful advertising sales executive for Time Inc., grew up in wealthy suburbs of New York, Chicago and Pittsburgh. An ancestor on his mother’s side, William Floyd, signed the Declaration of Independence. His Episcopalian Republican parents took seriously the Sermon on the Mount and encouraged benevolence to others. Born in 1952, the first of five children, Brown was the “goody two shoes of the family,” he said in an interview in his tidy home northeast of San Francisco in El Cerrito, Calif., where he lives with his spouse Myrna Santiago, the chair of the history department at a nearby Catholic liberal arts college.

Brown attended a fancy prep school, St. George’s in Newport, R.I., with a Rockefeller and a du Pont as classmates. He described himself as “not a popular guy in prep school. I wasn’t an athlete. I wasn’t part of the cliques. I was an outsider who identified with outsiders.” A formative experience came in 1969, the summer before Brown’s senior year, when he went off to an American Field Service volunteer program in Pipestem, a small town in southern West Virginia.

“What struck me was there were a lot of poor people,” he said. “I’d never seen poor white people. They worked very hard. The poverty wasn’t from lack of moral character or lack of drive. West Virginia was rich in terms of resources but they were owned by banks in Pittsburgh and New York City. That struck me as unjust.”

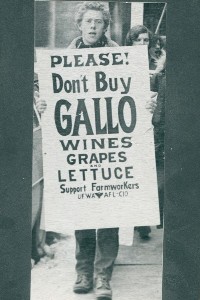

|

| Garrett Brown, as a college student in 1975, supporting a grape boycott promoted by the United Farm Workers union. |

His idealism kindled, Brown went off to college amid the social turbulence that continued from the 1960s into the early 1970s. He took off a year to drive a Checker Cab in Boston, before graduating from the University of Chicago in 1976. A student of 20th Century American history, Brown wrote a thesis on the transition of the United Auto Workers from a social movement union in the 1930s and 1940s to a more pragmatic labor organization.

After his newspaper and factory jobs, Brown decided that he wanted to observe social change up close, and headed to a Spanish language school in northern Nicaragua, in a stronghold of the leftist Sandinista movement. When an idealistic young American engineer working on a hydroelectric project in Nicaragua, Ben Linder, was killed in 1987 by the Contra rebels fighting against the Sandinista revolution, Brown was motivated to learn technical skills to carry on in Linder’s spirit.

That eventually took him to a two-year graduate program at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health, where Brown received his master’s degree in industrial hygiene in 1991.

“Garrett came to the School of Public Health knowing what he wanted to do and where he wanted to do it,” said Robert Spear, then acting dean and now a professor emeritus. “It’s the kind of field that draws socially conscious people.”

“Of all the students I’ve seen in that general field, I cannot think of anyone who was more committed to the welfare of the worker, particularly the people in the dirty jobs,” Spear added. “Those people can’t complain or make a stink about it, or they’ll get fired. He’s got to be one of an elite group in the field who knows what he’s talking about.”

Two years after graduating from Berkeley, Brown arrived at Cal/OSHA. Yet he also continued his work as an activist. Just as he was settling into his new state job, Brown took the lead in founding the nonprofit Maquiladora Health and Safety Support Network. He still works for free for the network, which includes 400 industrial hygienists, toxicologists and other specialists who advise factory workers battling hazardous conditions at plants in Mexico, Central America, Indonesia and China.

Likewise, this March Brown went to Bangladesh to examine working conditions in that nation’s huge but notoriously hazardous apparel manufacturing industry. He also spoke at a conference on factory safety at the invitation of a top official of the Bangladesh Accord for Fire and Building Safety. The agreement was signed by more than 150 apparel companies and retailers from more than 20 countries after the April 2013 Rana Plaza catastrophe near Dhaka, Bangladesh, in which a factory building collapse took the lives of more than 1,100 people and hurt 1,800 others.

On returning to Northern California, Brown gathered with professional colleagues to speak about the aftermath of the disaster.

“It’s totally scandalous,” Brown told the group. “No U.S. brand has offered a dime of compensation. Forty percent of the factory owners are not paying the new minimum wage of $67 a month for a 60-hour work week,” he said, basing the figures on reports from Bangladesh manufacturers and exporters who say they can’t afford the cost.

“I’ve been in some poor places. Bangladesh takes the cake,” he said.

In his career at Cal/OSHA, Brown took satisfaction in pursuing some of the agency’s toughest and most complex cases.

One example he points to the investigation of AXT Inc. in Fremont, Calif. In 2000, Brown said he discovered that its workforce – consisting mainly of newly arrived immigrants who didn’t speak English — was being exposed to dangerous levels of arsenic. “They were slicing and processing gallium arsenide wafers, eating and drinking in the work area and taking the dust home to their families,” he said. The semiconductor plant was shut for four days while improvements were made. Under a deal later negotiated with the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, the company paid $198,655 in fines.

In 2006, Brown investigated injuries to pile drivers rebuilding the eastern span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. KFM, a consortium led by Kiewit Construction Co., claimed an excellent safety record. But Brown, who conducted 40 interviews over six months, determined that workers were pressured to remain silent about injuries. As Brown recounted in an article he co-wrote on the case, the bosses for years slipped crisp new $100 bills into the pay envelopes of crew members who reported no injuries. Brown, however, identified at least 13 serious unrecorded injuries, including sickness from welding fumes and a head injury from a fall off a flatbed truck. The employer was able to get the citation downgraded, and it paid a fine of $5,790.

Even though charges often are reduced and fines modest, Brown said, he felt that his work paid off in this and other cases. “I had an opportunity to identify hazards and get them fixed, so people wouldn’t get injured or killed,” he said.

Berkeley lawyer Ellen Widess, who as Cal/OSHA chief from 2011 to 2013 made Brown her special assistant, praises his work. He was, she said, “one of the finest inspectors that Cal/OSHA has ever had” and she lauded his “fearlessness in telling it like it is.”

While Brown served in his leadership role at the agency, Widess elaborated, he improved the skills of other inspectors. “He knew the vast array of OSHA standards. He has an encyclopedic mind. And he was inspiring. Doing the work you do at OSHA, you need the inspiration. You’re turned away at workplaces, and have to fight for every bit of information on how an accident or illness happened. He handled the hardest cases. He was tenacious in holding on and ensuring that we got a fair result.”

| “He is so focused and so passionate about worker safety that he sometimes misses the bigger picture. He will not credit the employer for doing everything an employer can reasonably do to prevent accidents and illness." |

But attorney Fred Walter, who specializes in defending employers charged with Cal/OSHA violations, gives Brown a mixed assessment. “Garrett’s investigations are the most thorough, the most professional of anyone I have worked with at Cal/OSHA. When he writes an investigation report, it’s airtight. Anytime Garrett was assigned to a case, we’d have to bring our A game,” Walter said.

At the same time, Walter said, “He is so focused and so passionate about worker safety that he sometimes misses the bigger picture. He will not credit the employer for doing everything an employer can reasonably do to prevent accidents and illness. He will find a way to place liability on the employers.”

While calling Brown a “dedicated and knowledgeable worker health and safety advocate,” long-time colleague Clyde J. Trombettas, a Cal/OSHA district manager, said in a letter to the editor of a workplace safety publication that Brown’s critique of the agency is over the top. He “leaves the impression that Cal/OSHA is on its last legs and barely breathing,” wrote Trombettas, who declined to be interviewed for this story.

Widess said Brown also drew criticism from her former boss, Christine Baker, director of the Department of Industrial Relations, which is Cal/OSHA’s parent agency. Widess said Baker viewed Brown as “too negative, too aggressive in terms of enforcement and in terms of his public comments about understaffing.” Powerful business interests angry over his comments would complain to Baker, who in turn told Widess that Brown wasn’t an appropriate person to represent Cal/OSHA.

Baker, for her part, denied ever telling Widess that Brown was too aggressive, or that she received complaints about him from business interests. “No company came to me and said, ‘We don’t like Garrett Brown,’” Baker said in an interview.

She called Brown “very intelligent,” “an expert in his field” and “very dedicated,” but added: “He is not an administrative expert. He’s not management oriented.” In addition, Baker faulted Brown and Widess for flouting protocol by releasing information to legislative aides without authorization and for failing to understand the state budget process. “You can’t just wave your hands and come up with the money. No matter how many times I said that, they didn’t get it, or didn’t want to get it.”

When Widess was forced out of her job in September, Brown regarded it as emblematic of backpedaling by the Department of Industrial Relations, and he decided it was time to take early retirement. Brown had admired Widess’ tough approach to enforcement. As he put it, “No backroom deals. No kid gloves for politically connected companies with Ellen.”

Brown soon struck back, first by writing his report arguing that Cal/OSHA had been put on a “starvation diet” by Baker and California Gov. Jerry Brown, leaving it severely understaffed. By his count, the agency had 170 field inspectors as of the end of 2013 — one for every 109,000 workers, well below Oregon’s one for every 28,000 workers and Washington state’s one for every 33,000 workers.

| Baker and other Department of Industrial Relations officials disputed Brown’s argument that Cal/OSHA has fallen short in protecting workers, and cited as evidence figures showing decreases in California workplace injuries and fatalities from 2003 to 2013. |

Brown’s report was the basis of a complaint that the watchdog group PEER, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, filed in February with the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The complaint, which remains under investigation, accused Cal/OSHA of failing to maintain the staffing levels required to receive federal funds and said the state has one of the worst inspector-to-worker ratios in the nation. “California leads the nation in many areas but worker safety, unfortunately, is not one,” said Jeff Ruch, PEER’s executive director.

Baker and other Department of Industrial Relations officials disputed Brown’s argument that Cal/OSHA has fallen short in protecting workers, and cited as evidence figures showing decreases in California workplace injuries and fatalities from 2003 to 2013. They also noted that the new state budget calls for increased staffing that would bring the number of field inspectors to 204, and said Brown didn’t take into account management changes already made that are improving performance. As Baker put it in a March letter to a state lawmaker, “California is using its worker health and safety resources strategically.”

In the whistleblower claim Brown filed with the state auditor in April, which also remains under investigation, Brown accuses the Department of Industrial Relations of sitting on, or diverting, Cal/OSHA money. For instance, he said the department failed to use a surplus in the Elevator Safety Fund for inspections even though more than one-third of the state’s elevators operate under expired permits and await examinations.

In an email, the department didn’t deny the assertion about the elevator fund, saying its “understanding of the extent of the current backlog and the emergence of the current surplus in the Elevator (Safety) Fund are relatively recent developments,” and that Cal/OSHA now has been directed to resolve the problem.

Brown isn’t swayed by the Department of Industrial Relations’ arguments, particularly when it comes to staffing, which he says will remain inadequate even if the positions authorized under the new state budget are filled.

Still, he isn’t counting on getting any major help from the powers that be in Sacramento. “Occupational safety and health has almost no friends,” Brown said.

About FairWarning

FairWarning (www.fairwarning.org) is a nonprofit, online news organization focused on issues of safety, health and government and business accountability.

Recent articles by Garrett Brown on ISHN.com:

Former Cal/OSHA staffer says he witnessed political coup that forced out agency head

Why you should care about Cal/OSHA’s budget and political troubles