Across the country, the shale boom has given rise to fears about whether oil and gas development might be polluting the water we drink and the air we breathe. This has led some residents to try doing their own field research, in the mode of “citizen science.” But unlike the annual Christmas Bird Count or a website to help astronomers catalog billions of galaxies, their work is a tricky blend of science and advocacy.

Joanne Martin stands on the muddy bank of Brady Run, a stream in Beaver County in western Pennsylvania. To get there, she crawled down a steep gravel slope, ducking low tree branches and stepping over dead brush.

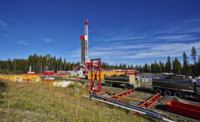

Martin has been coming to Brady Run for three years to test the water for signs of pollution from natural gas drilling. There’s a producing well pad just about a half a mile from here.

First, Martin plunks in a wooden measuring stick to check stream depth.

“Then, I go upstream a little bit because I don’t want to take water from where I disturbed the sediment,” she says. “I don’t want any of that in the sample.”

She takes a small cup, the kind you might use at a doctor’s office, and dips it into the stream, bracing herself for the icy water.

Back on the bank, Martin uses a pocket-sized monitor to test her sample. It’s measuring the conductivity of the water. A higher conductivity reading than usual could be a sign that metals are discharging into the stream, possibly as the result of a spill of the salty flowback water that comes up out of a well after it has been hydraulically fractured or fracked.

Source: http://stateimpact.npr.org