|

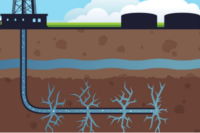

| Coal-bed methane gas drilling in Wyoming's Powder River Basin was responsible for nearly 3,000 new wells annually for a period in the mid-2000s. In this photo, crews used a small drill rig to reach coal-beds only a few hundred feet down. (Courtesy Wyoming Bureau of Land Management's Buffalo field office) |

If there’s not an abrupt change of course in Wyoming’s rate of workplace fatalities, the Cowboy State is on track to lose 36 workers to on-the-job deaths this year. They will leave behind wives, husbands, daughters, sons, parents and friends — the type of tragedy that devastates families. Wyoming’s working families have lived with this reality for more than a decade while state lawmakers consistently resist more safety enforcement and stiffer penalties.

This year, Gov. Matt Mead and Wyoming lawmakers again rejected those calls from worker advocates. Instead, they have doubled down on a strategy that, for a decade, doesn’t appear to have improved Wyoming’s workplace fatality rate — consistently the worst or close to the worst fatality rate in the nation. Rather than add teeth — enforcement and liability — Wyoming is offering up more voluntary “courtesy inspections” and a new pot of grant money to employers who want to create or improve their own safety programs.

According to some Wyoming leaders, it is only through cooperation, education and training that Wyoming can build a true “culture of safety.”

“I don’t believe that penalties deter. I think that nobody wakes up in the morning and says, ‘I’m going to hurt my co-worker Bob today.’ … Because lots of people don’t believe they’re going to hurt a co-worker, the penalties aren’t going to be a threat to them. When the penalties come to play, the cow’s already out of the barn,” said Rep. Tom Lubnau (R-Gillette).

This year the Wyoming Legislature passed HB 89 (sponsored by Lubnau), which will arm the state’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration with seven new full-time safety consultants strictly dedicated to the agency’s long-existing voluntary courtesy inspection program. For years, Wyoming’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration has offered courtesy onsite inspections, which employers can request, voluntarily, to gain advice on how to come in line with safety regulations — without the threat of citations for discovered violations. Those new inspectors will not be allowed to perform spot inspections or enforcement duties. The bill also sets aside $500,000 in grant money available to employers who want to establish or improve their own safety programs.

The grant program requires that the employer receiving a grant match at least 10 percent of the funding. No grant would exceed $10,000. It would also require that grant recipients report to the state the number of employees killed and injured for the next five years.

Gov. Mead did create one additional enforcement position at Wyoming OSHA, and the agency will have a total of nine enforcement officer positions this year. Yet Wyoming’s overall strategy to curb workplace fatalities still falls well short of the additional enforcement- and penalty-based proposals supported by worker advocate groups. For the past decade, the agency’s six inspection officers represented an inspection rate capacity of just one onsite job inspection per employer every 60 years. Some worker advocates see HB 89 as an acknowledgement that this is the last opportunity for Wyoming to significantly reduce workplace fatalities and injuries before politicians finally are forced to use the stick as well as the carrot.

“Our position here is we’ve been describing this as a strong first step. It puts private employers on notice, particularly in these most dangerous industries — oil and gas, in-situ mining and construction — that we’re giving you a chance here to come up to snuff with your operations,” said Dan Neal, executive director of the Equality State Policy Center (ESPC), which represents several unions and conservation groups.

The success of HB 89 and Wyoming’s ongoing voluntary approach to improving workplace safety will be measured in how many companies take advantage of Wyoming OSHA’s beefed up courtesy inspection and safety grant programs this year. On average, only 2 percent of Wyoming’s employers call on OSHA for courtesy inspections. Success will also be measured in how many workers are maimed and killed on the job.

In a March press conference, Gov. Mead said he intends to give the current strategy at least a year before considering more spot inspections or higher penalties for proven safety violations. HB 89 does include several reporting provisions to measure the success of the programs, and will be up for review in 2014.

“It depends on how it’s going,” said Mead. “If it has no noticeable effect, the timetable would be moved up, obviously. We have to do better. … If it looks like we’re not making any progress, then we’d have to be more aggressive, including, possibly, higher fines.”

|

| Construction for coal-bed methane development. Miles of pipeline and other construction were part of Wyoming's coal-bed methane gas play. (Courtesy Wyoming BLM Buffalo field office? |

Reactions to the ‘Ryan’ report

Like Lubnau, a majority of Wyoming lawmakers staunchly oppose increasing spot safety checks and fines for serious safety violations, for fear it would stifle business and saddle well-meaning employers with punitive fines. Fiercely pro-industry, most Wyoming leaders tend to believe that workplace safety is a matter best left to employers, with minimal government involvement.

“You can have a $50,000 penalty, and you‘ve got somebody dead and somebody out of business,” Lubnau told WyoFile.

Lubnau said the cooperative nature of HB 89 comes from his research of the aviation industry’s successful approach to improve its safety performance from the 1970s to the 1990s and beyond. He said the industry studied years of data to identify behaviors and trends leading to aviation accidents and then focused on improving those areas of risk. He believes the same approach can be applied to Wyoming’s most dangerous workplaces; construction, oil and gas, and transportation.

Construction for coal-bed methane development. Miles of pipeline and other construction were part of Wyoming's coal-bed methane gas play. (Courtesy Wyoming BLM Buffalo field office — click to enlarge)

According to a 2011 state-level report, an overwhelming percentage of Wyoming’s workplace fatalities were the result of not following existing safety rules, including the use of seatbelts.

“You’ve got to look at it as a step-by-step process. It takes a culture change to get there, and we have got cultural problems in our workforce,” said Lubnau.

Wyoming leaders have been under pressure for years to improve the state’s awful workplace fatality record. But it was a report in December by former state occupational epidemiologist Timothy Ryan that underscored the severity of the problem and finally made it politically acceptable to address the issue through legislation.

Timothy Ryan’s report verified what many worker advocates had suspected all along; the blame lies with employers and employees alike. And despite some gradual trends toward better safety performance, standards are disjointed, unevenly applied and rarely enforced.

After speaking with “hundreds of employees” in a variety of industries in Wyoming, Ryan said this is how workers described their typical work environment:

— “There is a breakdown in communication between upper management, supervisors, and employees regarding safety.”

— “Often the safety training that we receive is not enforced on the worksite.”

— “Employees are told to ‘get the job done’ and safety protocol and rules are not enforced, resulting in injuries and fatalities.”

— “On any one job-site, there can be a wide range in the safety standards.”

Ryan also found that from 2001 to 2008 non-fatal occupational injuries declined from 5,600 per 100,000 full-time workers to a rate of 4,000. But serious injuries — those that require hospitalization — remained a growing problem over the same time period. Approximately 700 workers per year were injured seriously enough to require hospitalization. The number of serious burns remained steady, and amputations were on the increase — from 10.1 per 100,000 workers to a rate of 14.7.

The idea for additional courtesy inspections came straight from the Ryan report. Ryan also recommended the need to continue and expand on current partnerships between industry and government agencies. For example, the Wyoming Oil and Gas Industry Safety Alliance (WOGISA), formed several years ago and in 2011 it formally partnered with Wyoming OSHA to institute a series of “best practices.”

Ryan also stressed the need for better information gathering and sharing among agencies so that workplace injury and fatality trends can be more quickly identified.

Ryan resigned the day after submitting the report in December, and later told the New York Times, “The current Legislature is not interested in any new regulations that have to do with safety. … It got to the point where I wanted to see the action that’s connected to these findings, and I decided it wasn’t happening at a pace I was comfortable with.”

While worker advocacy groups such as the Equality State Policy Center, the Spence Association for Employee Rights (SAFER) and Wyoming AFL-CIO enthusiastically supported HB 89, they also say they’re not giving up on reforming enforcement, penalties and liability as part of the overall strategy to decrease deaths among Wyoming workers.

“We are starting with the path of least resistance. In theory, it’s (HB 89) great. We see it as part of a package. … The legislation shows the least painful, most palatable way to start addressing a problem,” said Mark Aronowitz, staff attorney for SAFER.

And groups such as WOGISA are not opposed to stiffer penalties and increased enforcement. In fact WOGISA, with a membership of more than 200 oil and gas operators and service companies, has already advocated for those measures and a tougher seatbelt law in Wyoming.

As for adding more courtesy inspectors at Wyoming OSHA, at least one drilling company has said it’s a welcomed move. Patrick Hladky, owner of Cyclone Drilling in Gillette, said he believes too many employers in Wyoming have been discouraged by the long wait time for courtesy inspections.

“We’ve tried in the past, and nobody shows up until months later,” said Hladky, adding that he believes more employers will take advantage of the beefed up courtesy inspection program.

Neal, of the Equality State Policy Center, said the courtesy inspection program is an excellent tool, but it likely suffers entrenched perceptions regarding OSHA.

“The whole idea here is some people just don’t know the law very well and they’re afraid to call OSHA to see where they’re not in compliance. You can do that and have the most egregious errors pointed out to you,” said Neal.

Lubnau said he will likely introduce another workplace safety bill in the next legislative session, this time enticing employers to participate in a self-reporting program to help build a good database on workplace injuries and fatalities. Incentives could include reduced workers’ compensation premiums, he said.

In the meantime, Wyoming AFL-CIO and SAFER say they will continuing pushing the set of recommendations they submitted to the governor and state lawmakers earlier this year. Their four main recommendations:

- Mandatory post-injury inspections and increased spot inspections.

- Increased penalties for employers and employees who discourage reporting injuries “to protect safety awards, bonuses, and other performance incentives, or to avoid lost time accidents which can potentially lead to increased Workers’ Compensation premiums.”

- Require that company injury records be made public, much like under the Mine Safety and Health Administration.

“I differ with some lawmakers and the governor when they say we want more carrot than stick,” said Aronowitz. “I don’ think the stick is the most important thing, but it’s the threat of the stick. … We don’t drive 100 mph all the time because there’s a threat of the speeding ticket. I do think increasing penalties does have a deterring effect.”

However, Lubnau said he believes that the more buy-in from big companies on creating a culture of safety in Wyoming, the more it will squeeze out the operators and contractors who are bad actors.

“The ultimate plan is get the bad actors to adopt a safety plan or to go out of business,” said Lubnau. “No amount of enforcement is going to drive a bad actor out of business.”