In many cases, we need to change our self-perceptions to meet these kinds of goals. Maybe we don’t think of ourselves as the kind of person who can diet, work out, or work safely. It could be because our actions or behavior up to this point show that we don’t do these things well.

Think about how much our behaviors define and label us. We observe ourselves doing

certain things and use that behavior to define who we are. Then we might attempt to live up to that self-perception through follow-up behavior. And if that behavior involves taking risks, cutting corners, or otherwise acting unsafe, you can see the potential consequences in the workplace.

Self-perception theory

The notion that we define who we are from our behaviors is founded in the teaching and research of B. F. Skinner and the follow-up scholarship of Daryl J. Bem, an eminent professor of psychology at Stanford University. Dr. Bem developed a comprehensive theory of self-perception based on the premise that, “Individuals come to ‘know’ their own attitudes, emotions, and other internal states partially by inferring them from observations of their own overt behavior and/or the circumstances in which this behavior occurs” (from Bem’s 1972 book chapter entitled,Self-Perception Theory).According to Bem’s theory, when we want to know how we feel, we look at our own behavior and the circumstances surrounding it. We eat too much and say, “I must have been hungrier than I thought.” We play a poor tennis match and conclude, “I’m not as good at this as I thought I was.” Or we go out of our way to help another person and think, “I must care more than I thought I did.”

Power of circumstances

Research has demonstrated how circumstances and behaviors influence our emotions, attitudes, and moods. In classic research by Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer in 1962, experimental subjects were given injections of epinephrine or adrenaline, which made them feel physically aroused. Then these subjects waited individually with one other person who presumably had received the same injection. Moments later the experimenter returned and asked the two individuals to complete a questionnaire about their feelings.What emotion did these subjects experience? The physiological arousal was the same for every subject, but some reported extreme anger while others said they were very happy. Why? The subject’s own behavior and that of the other person in the waiting room, who was actually a research assistant, determined whether the subject felt extreme anger or joy.

During the waiting period, the research assistant, posing as another subject, acted in one of two ways. In the “euphoric” condition, he threw paper airplanes, shot crumpled balls of paper into a wastebasket, and twirled in a hula hoop. He encouraged the subject to join in the fun, and most did.

In the “anger” condition, both individuals were asked to complete a questionnaire while waiting for the experimenter to return. The questions were intimate and quite inappropriate, especially the question, “With how many men has your mother had extramarital affairs — four and under, five to nine, or ten and over?” When the research assistant read this question he ripped up his survey in a fit of rage.

Schachter and Singer showed that emotional reactions are shaped by the behavior that people observe in themselves and in others. In another series of studies, subjects’ emotions were manipulated by giving them false auditory feedback about their heartbeat. When they presumably heard their heart beating faster they felt more sexually aroused or fearful, depending on other external events.

It’s possible to change self-perception by altering external conditions. Think about what this means for our work in safety. We can act ourselves — or others — into thinking or feeling a certain way, perhaps a safer way.

Setting the stage

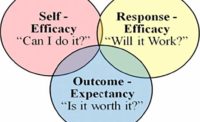

I don’t mean to imply that behavior always precedes and influences thinking. In fact, it’s commonly believed that our personal motivation comes from within us, implying that we think ourselves into acting in certain ways.But suppose you want to motivate another person to do something, say to work safely on the job. How would you do it?

Even if you believe people can only truly motivate themselves from within, you can at least establish an external condition (or environmental context) that facilitates this inner motivation. Yes, you can do things to increase the probability people will do what you want. We’re talking about interventions, and they can vary from developing an external accountability system or incentive program to setting up opportunities for personal choice, ownership, or constructive interpersonal conversation.

I think the most efficient way to motivate certain action in others, such as working safely, is to set up circumstances or consequences (feedback processes, teams, rewards, etc.) that help people to act themselves into new ways of thinking. Their new behavior can influence a new way of perceiving themselves. This can lead to a new personal label and then to more behavior consistent with that label. “I’m wearing my safety glasses, so I’m a safe worker and I should also use all other personal protective equipment.”

A safety tool

It doesn’t matter which comes first — certain behavior or certain thinking. What matters is that we have a tool — we can improve safety by focusing attention on safe behaviors. When people see themselves working safely, they might change how they view themselves. They might act themselves into thinking of themselves as safety conscious, and thus motivate themselves to sustain the new behavior.I emphasize “might” because not all behavior change leads to consistent changes in thinking and self-perception. We know intuitively that concepts like “personal control,” “empowerment,” and “ownership” determine whether our behavior influences supportive thinking, attitude, and self-perception. Hold on to this thought. My ISHN contribution next month will clarify this critical point, and explain what we can do about it.

For now, appreciate the potential of your own behavior to define who you think you are. So get going on those New Year’s resolutions. Your actions can initiate a self-motivating spiral of behavior feeding thinking, thinking motivating more behavior, and so on. Then, accomplishing your New Year’s resolutions will define the better person you have become.