Every reader has heard the term "feedback," and probably realizes the critical connection between behavioral feedback and behavior-based safety (BBS). Indeed, peer-to-peer safety coaching with BBS feedback is key to the documented success of BBS at reducing the total recordable injury rate (TRIR) of numerous companies worldwide. And most readers realize the success of BBS feedback depends on how it’s delivered.

Guidelines for effective delivery of BBS feedback can be summarized with the words--Specific, On time, Appropriate, and Real--whose first letters spell "soar."

Specific

Feedback must focus on specific behavior. As a consequence (for motivation), feedback specifies what behavior to stop and what behavior to keep performing. But as an activator (for direction), it’s not feedback but feedforward. Feedforward reminds an individual to perform a particular task in a certain way.

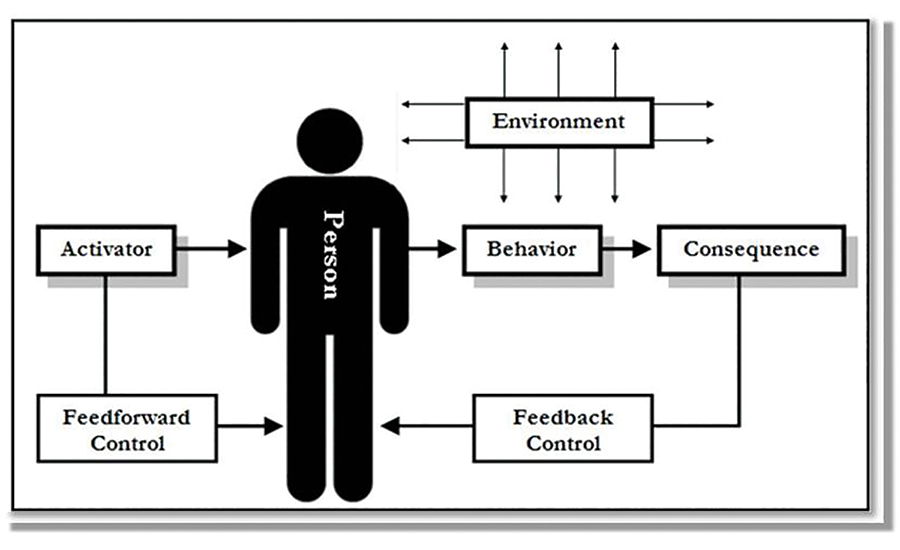

The illustration shows the activator-behavior-consequence (ABC) model of BBS. Note the distinction between feedforward and feedback. Both of these behavior-improvement techniques need to be understood and accepted. Thus, a "person" is depicted between the Activator (feedforward) and Behavior, and between the Consequence (feedback) and Behavior.

On time

Motivational feedback to increase or decrease the occurrence of behavior should follow the target behavior as soon as possible. An excessive delay can be counterproductive.

But when the purpose of behavioral feedback is to shape the quality of a response, it usually makes the most sense to give such directive feedback as an activator (feedforward) that precedes the next opportunity to perform the target behavior.

Receiving feedback about an error as a consequence can be perceived as punishing and frustrating, if an opportunity to correct the observed error is not available in the near future. When the feedback recipient eventually has an opportunity to correct the behavior, the advice might be forgotten.

Advice to improve a behavior should be delivered as close as possible to the next opportunity for the behavior to recur. This timing of feedforward optimizes its directive influence and reduces the potential of a negative attitude resulting from catching a person making a mistake.

For example, you observe a co-worker walking hurriedly down a flight of stairs without using the handrail. Should you provide corrective feedback?

It's obvious this individual is in a hurry, and would not appreciate a conversation about handrail use at this time. Plus, you might feel awkward providing corrective feedback, with no credible opportunity to buffer the negative with relevant positive words. The solution: offer behavioral feedforward.

In this case, “on time” means you wait for an opportunity to provide this employee with a feedforward reminder to use the handrail before s/he uses a flight of stairs. Yes, it may take some time before you can seize the feedforward moment. You might see an opportunity for this pre-behavior reminder when you are walking with a group of co-workers. You simply say, "Let's remember to use the handrail."

Appropriate

Feedforward and feedback should fit the situation. Both should be expressed in language the performer can understand and appreciate, and it should be customized for the recipient’s skill to perform the particular task.

When people are learning a task, directive feedforward and motivational feedback need to be detailed and perhaps accompanied with a behavioral demonstration. It's important to match the advice with the performer's achievement level. Don't expect too much and give more advice than an individual can grasp in one feedforward exchange.

At times, risky behavior is performed by experienced workers who know how to do the job safely, but may have developed at-risk habits or are taking a shortcut for efficiency. It could be insulting to give these individuals detailed instructions about the safe way to complete their job. It’s best to give feedforward as a reminder to take the extra time for safety. Preceding your reminder with the words, "As you know," could increase acceptance of the reminder.

It's important for the BBS coach to size up the situation, and make specific and timely feedforward or feedback fit the occasion. This is not easy, and requires up-to-date awareness of the performer's knowledge and skill regarding a certain task. It also requires specific knowledge regarding the safe way to perform the task. This is a prime reason why the most effective BBS feedforward and feedback usually occur between employees on the same work team.

Real

Feedforward and feedback will be ineffective if the verbal behavior is viewed as a way of exerting top-down control, or demonstrating superior knowledge, competence, or motivation. Behavioral feedforward or feedback is only given to improve and maintain the safe competence of team members.

Corrective feedback is most likely to be perceived as genuine or "real" when it occurs between work peers on the same team. These individuals know most about the situation and the person, and have sufficient information and opportunity to make the feedforward and feedback specific, on time, appropriate, and real. They are best able to make their behavioral feedforward and feedback: a) specific in terms of behavior to initiate, continue or stop; b) appropriate for the knowledge, abilities, and experiences of the performer; and c) reflect real concern for the individual's safety, and d) on time.

In summary

When using feedforward, consider this communication a reminder or an activator. In contrast, feedback is most effective when it can be delivered soon after safe behavior has occurred and enables the recipient to feel valued and appreciated, rather than de-valued and unappreciated.