There has been lots of ground covered so far: hazardous energy and movement; three sources of unexpected events (over 95% in the Self-Area); the counter-intuitive nature of dangerous activities vs. actual outcomes; and then why. When both our eyes and mind are not on task, for that moment, we are defenseless.

As mentioned in an earlier article, it’s not that we are totally defenseless, it’s that from time to time, we are momentarily defenseless, which is why you hear so many people talking about car wrecks or serious injuries, saying “I really wasn’t doing anything wrong, I wasn’t really speeding or rushing.”

So, figuring out “when” becomes the crux of the matter. Unless we know when those moments will happen, knowing why we get hurt badly won’t help to prevent the next one. So, figuring out the “when” part is the key. Unfortunately, for so many years, the focus has been on “what” the people were doing and how much hazardous energy they were dealing with. When will we be most likely to make both critical errors at the same time, where there is also a significant amount of hazardous energy involved?

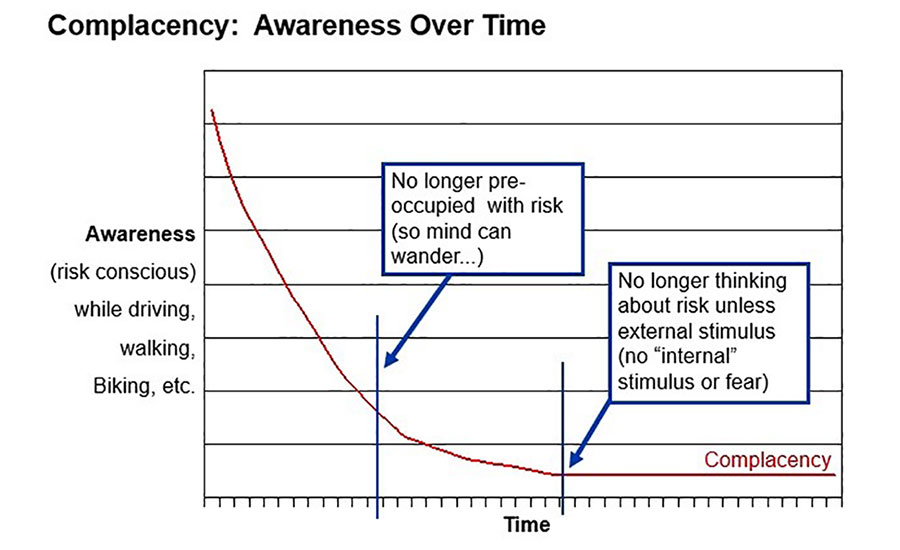

It will likely be doing something that you have been doing for a while, because at the beginning of any activity where there is a fair bit of hazardous energy the potential for injury is very high (see Figure #1).

First stage of complacency

During this first period of time with an activity or skill it is quite natural to be able to self-trigger on the amount of hazardous energy. As a result, it’s easy to stay focused. It may even seem that it would be impossible to become complacent. However, as we all know, the initial fear rarely lasts forever. Over a period of time, we come to the first stage of complacency. This is where the fear or skill is no longer pre-occupying.

Even if you don’t have anything else you need to think about or want to think about, your mind can drift away. But if you’re rushing, chances are it’s for a reason. It might be because you want to get there early. More likely, it’s because you don’t want to be late. Either way, that’s what most people think about when they’re rushing — not what is the risk in the moment. And whether the consequences for being late are going to be really bad, such as being late for a work meeting.

So self-triggering on rushing — when the rushing is intense — is easy in terms of it not being difficult to notice. It’s easy enough to realize that you’re moving really fast or doing way too many things at once. What isn’t so easy is how compelling it is to let your mind go back to the reason you’re rushing or the problems being late will cause.

The same thing is true for frustration. When you’re really angry, it’s easy to recognize, so you can self-trigger, come back to the moment and make an effort to keep your eyes and mind on task. But depending on how much frustration, it might be difficult not to keep drifting back.

However, the good news is that if the state is intense, you can recognize it easily and self-trigger on it quickly. This is also true for fatigue. When you’re really tired, it’s easy to recognize. But the problem is that when you’re just a bit tired, it’s not so easy to recognize, and we all get tired here and there during the day so it’s not unusual. But if you now add a little bit of rushing and frustration with that fatigue, the combination of all three could easily be enough to cause mistakes, which will likely cause more frustration and usually more rushing.

So, the concept of self-triggering on the state may sound simple or easy enough to understand, but in reality it’s not always so easy. If you’re driving when your eyes are closed, or worse, you fall asleep for a few seconds, it’s easy to see the concept of being momentarily defenseless.

Unfortunately, it’s far too easy for most of us to relate. But we didn’t fall asleep at the wheel when we first started driving. It took a while before we would become complacent enough. Although nothing ever really stops us from reminding ourselves or thinking about the amount of hazardous energy and the potential for injury, it won’t happen naturally like it did at the beginning. However, once you pass the first stage of complacency, self-triggering on the state will be more reliable than trying to self-trigger on the amount of hazardous energy.

Second stage of complacency

As time goes on, we get to the second stage of complacency. By this time, there is no more internal fear, such as when we first started driving. However, if we nearly get hit by a big transport truck, then we will start thinking about the risk. But it required an external stimulus.

Another thing that’s interesting about this second stage is what it does to your decision-making. It’s fairly easy to recognize because you’ll likely hear something like this: “Oh yeah, well I’ve been doing it this way for 20 years and I’ve never been hurt.” And because they haven’t been hurt, they may not be motivated to change or to use an additional layer of protection. With some individuals, stubbornly refusing to change may be more apt.

At the second stage or beyond, unless the individual knows about self-triggering, then he or she will almost undoubtedly become preoccupied with why they are rushing or what will happen if they are late, who or what they are frustrated with, or when they can take a break or get some rest. In other words, mind almost totally off task.

It’s this high level of complacency that can affect their decisions with eyes on task. They can decide to look away from the road to pick up their phone or get something out of the glove box, and now you have another defenseless moment — when someone’s eyes and mind are both not on task for a second or two, or three or four. And although these moments of defenselessness may be happening more frequently as someone moves into the second stage of complacency, when their mind is mostly off task, chances are they won’t notice it unless something bad actually happens.

Difficult to self-trigger

I can remember when I first got into the safety business many years ago. I was selling safety videos and I couldn’t understand why I would keep hearing, “The young guys get hurt more than the old guys, but it’s the old guys that die.”

It was common knowledge that people got hurt because they didn’t have safety training or proper safety training, which is what our company was selling. I couldn’t understand why well-trained, experienced workers were experiencing so many serious injuries and fatalities. And I was hardly alone. It didn’t seem like anyone I met in management or the safety profession had a good explanation either.

In retrospect it’s all so simple: more time or repetition means more complacency, and more complacency means more defenseless moments when the person’s eyes and mind are not on task. And although older, more experienced workers may not be as inclined to rush as much as a young worker, they could easily be feeling a bit of each state every day, which makes self-triggering much more difficult.

So as mentioned earlier, when the state is intense, figuring out the “when” part is not difficult because the state is easy to recognize. But if the state isn’t intense or if there is more than one state involved, then it (the combination) might not be very easy to recognize. And if all four states are involved, then even if it’s just a bit of rushing — combined with a little frustration and a little fatigue — it can be very difficult to recognize and self-trigger quickly enough to prevent the error.

If someone asked you, “how much are you rushing, right now, on a scale of 1-10?” you could say, maybe a six, because you know you’re under a bit of time pressure. So even though you might not have noticed it yourself, if someone asked you the question, you could easily identify the times when you were in a bit of a rush, a little frustrated or tired. So the problem of the less intense state or combination of states is not insurmountable.

But you need to ask the question, especially for complacency as you can never really feel it in the moment. This process is called “rate Your state.” Most people are familiar with the 1-10 rating system. With rushing, 10 is going faster than you’ve ever gone before; 9 is as fast as ever before; and 1 or 2 is really slow or stopped. Same thing with frustration or fatigue: 10 is more frustrated than ever before and 9 would be as tired as you’ve ever been before. Complacency is a bit different. You could think of a 10 as concentrating very hard on something else like a problem at work while you were doing something else, such as driving to work.

Anticipating error

The main thing is not to worry about decimal point accuracy in terms of pinpointing your level of frustration or fatigue as being a 6.5 or a 7. What’s important is that you recognize that you are dealing with a bit of frustration and a bit of fatigue, which could increase the risk that you might say something negative to a co-worker or customer. We have a simple tool that will help us to recognize the combinations of states even if the individual states by themselves are not that intense. All we have to do now is try to figure out when we will likely be in these states, or when we will be in more than one of them at the same time.

The easiest and best person to answer this is you because we know when we normally get tired during the day. We know who or what normally gets us frustrated. We know what makes us rush, like just before shift change or just before leaving on a long trip. And we know what the worst-case scenarios would likely be in terms of most expensive mistake you could make or what would waste the most time, damage customer relations, etc. So we can anticipate the time or the times during the day that the states could cause us the most trouble in terms of safety, quality, production efficiency or customer relations.

All you need to do now is set an alarm so you can “rate your state” at that time. Even though the mistake or critical error is always unexpected, the states that cause them are not. We can anticipate when and where we will be in one or more of the four states. And if you set an alarm and then you rate your state at that time, even if it’s only a bit of rushing, or a bit of frustration combined with complacency, you’ll be much more aware and much less likely to get hit with your guard down when you make both critical errors at once.

If you make the effort to ask yourself these questions, then set an alarm to rate your state at those times, or you organize this into the pre-shift routine at work, you can minimize or prevent many of these moments of defenselessness. It will begin to occur after the first stage of complacency and will likely become more frequent after the second stage.

The question of “when”

When will we have these defenseless moments where our eyes and minds are not on task? And if you think about it or if you think about all of the injuries you’ve had, which is thousands if you count all the bumps, bruises, cuts and scrapes, there was probably a much stronger pattern in terms of “when” than there was for “what.”

Next Issue: Critical decisions influenced by rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency